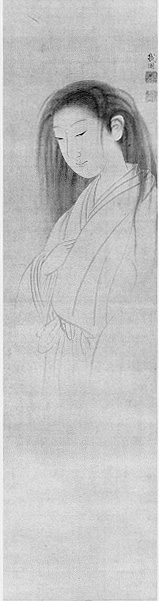

Translated and Sources from Mizuki Shigeru’s Mujara, Nihon no Yūrei, Inga Monogatari, and Other Sources

To learn much more about Japanese Ghosts, check out my book Yurei: The Japanese Ghost

Yūrei require a tether, something to connect them to the physical world, something strong enough to prevent them from moving on to the next world. Depending on the nature of this bond, a different type of yūrei can manifest. The bond of a mother to her child is one of the oldest and strongest of these tethers.

What Does Kosodate Yūrei Mean?

The kanji for the kosodate yūrei is descriptive. Kosodate (子育て) means child-raising. An alternate term substitutes amekai (飴買い) for the amekai yūrei meaning the candy-buying yūrei. Variations of the story can be found all over Japan, but most kosodate yūrei stories follow a consistent pattern.

The Legend of the Kododate Yūrei

There are multiple versions of the kosodate yūrei told all across Japan. Most of them follow an identical pattern. This version is told in Nihon no Yūrei by Ikeda Yasaburo as a personal recollection of a story that had been told to him:

“The name Tsukiji nowadays brings to mind a bustling fish market in Tokyo, but it was not always so. In the olden days, the area known as Tsukiji was packed with temples, mostly belonging to the Honkan-ji temple complex. The area was also covered in cemeteries.

Along the banks of the Sumida River that flows near Tsukiji, there were also stands selling fresh fish and the sweet sake for children known as amazake. In one story, late every night a woman clutching a child would come to a certain amazake dealer to buy the sweet sake from him, which she would then give to her child to drink. The sake dealer, sensing something mysterious about this woman, followed her from his stall one night and watched her as she made her way towards the main hall of the temple, where she disappeared like a blown-out candle. When she vanished, the sake dealer could hear the cry of a baby coming from somewhere in the cemetery. Tracking the sound to a freshly-dug grave, the sake dealer enlisted the help of some others to dig up the grave, and when opening the coffin discovered a crying baby nestled in the arms of its mother’s corpse.”

The legend has its origins in China, where it can be traced back to the book Yijian zhi (1198; Records of Anomalies), with the story of the mochikae onna, the rice cake-buying woman:

“One time, a woman who was pregnant died, and was buried in the ground. After that, a nearby rice-cake dealer began to have a strange customer come night after night, an odd woman carrying a baby. The woman always bought a rice cake for the baby. The dealer was suspicious, and stealthily tied a red string to the woman the next time she came in. After she left, he followed the red string and found that it led to a grave hidden under some bushes. After telling the bereaved family, they dug up the grave to find that the woman had given posthumous birth in her coffin. The bereaved family happily took the child to raise, and had the mother’s body cremated.”

Rokumonsen – Six Coins to Pay the River Crossing

Another part of the kosodate yūrei legends are the use of rokumonsen, the six coins placed with dead bodies in order to pay the toll across the underworld River Sanzu. In many versions of this legend, the kosodate yūrei is using these coins. Often the story continues for five nights, until the body is dug up and the final coin is found resting in her dead hand.

Many other merchants receive even less. In several of the tales, the mother uses the tanuki trick of passing off leaves as coins, and the merchant is left with only a wallet of foliage after the true nature of the woman is discovered.

But coins or leaves, the loving mother rarely buys food for her child, no rice or nourishment, but often the small sweet candies or toys that a child would crave, caring more for the baby’s happiness than its welfare.

Kosadate Ame

Kosodate yūrei remain a popular figure in Japanese folklore. To this day, a small shop in Kyoto still sells kosodate ame—child-rearing candy—and claims to be the very shop where the kosodate- yūrei came to buy candy.

Translator’s Note:

The kosodate yūrei is so similar to another type of ghost—the ubume—that they can almost be considered a different name for the same spirit. There are differences, however. The ubume is closely associated with blood, and with the Buddhist hell of Chi no Ike, the Lake of Blood, where women who died while pregnant were said to be consigned. Ubume also try to get someone to hold their baby, which kosodate yūrei never do.

Recent Comments