What are Kaidan?

Kaidan is a genre that has persisted in Japan for as long as the known history of Japanese literature. The popularity of kaidan, although that has not always the name been associated with the genre, has had its ebbing and flowing over the centuries, but never entirely disappeared, vanishing only for a short time until a new generation rediscovers these classical tales of the weird and mystifying.

The word kaidan should not be confused with horror or any other Western genre, or even the popular j-horror genre that came from Japan in the late 1990s. The word carries with it a specific nuance, and is used in Japanese for only a particular type of story, not for general ghost or monster stories. Nakata Hideo’s (中田秀夫; 1961 – ) film Ring (リング; 1998) is not kaidan, nor is Shimizu Takashi’s (清水崇; 1972 – ) film Ju-On (呪怨,; 1998).

In fact, many kaidan are not intended to be frightening at all. The stories can just as easily be funny, or strange, or just telling about an odd thing that happened one time. This element of kaidan often confuses Westerners, and a common complaint heard about yūrei stories is that they “aren’t scary.” This is because they are not intended to be. They are kaidan.

The Definition of Kaidan

Translators have always had a difficult time deciphering the word. Kaidan often ends up as ghost stories or mysterious tales or some such variation simply due to lack of options. Animated TV series like Gakkō no kaidan (学校の怪談; School Kaidan) (2000) wind up in English as Ghosts at School or Ghost Stories, neither of which captures the nuances and cultural impact of the word.

The best way to grasp the meaning of the word kaidan is by deconstructing the kanji that make up its composition.

The first kanji in kaidan, 怪 (kai), means weird, strange or mysterious. Like the kanji 霊 (rei), 怪 is a kanji that makes several appearances in Japanese folklore, the most important being in the aforementioned word 妖怪 (yōkai) which combines 妖 (yō) meaning attracting or bewitching with 怪 (kai). Yōkai is the term used for Japanese folkloric monsters like the water-dwelling kappa and mountain-dwelling tengu. The second kanji in kaidan is 談 (dan), means to discuss or talk. The kanji carries the nuance of transference of information, of passing from one mouth to another, and is found in words such as 雑談 (zetsudan) meaning idle chatter.

The most literal possible interpretation of kaidan would be something like a discussion or passing down of tales of the weird, strange or mysterious. Personally, I prefer to either use the word as it stands, kaidan, or if I must put it into English I take a page from Irish author Sheridan Le Fanu, most famous for his lesbian-vampire story Carmilla (1872), and who called his stories of the supernatural and sublime weird tales. I like the term weird tales for both the nostalgia it invokes and the nuance of the type of story the reader expects, somewhat similar to kaidan.

Kaidan or Kwaidan?

A large number of translators and authors through the years have chosen to preserve the word kaidan in English, although the spelling depends on the era in which you are translating. Most modern translators use the Hepburn system of romanization, first published in 1887 by James Curtis Hepburn in the third edition of his Japanese–English dictionary. The Hepburn system was specifically designed to make Japanese more easily pronounceable to English speakers. Other systems, such as the Nihon-shiki romanization, are designed for use by native Japanese speakers with words that approximate the sounds better, but are more confusing to English speakers.

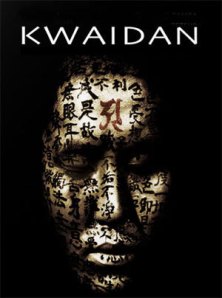

Older translations used a different system of romanization, one that preferred a kw sound instead of a hard k. This method of translation results in the term kwaidan, which was used by Lafcadio Hearn for his 1904 book Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things. In modern times, the kw form of kaidan has become synonomous with Hearn’s work, and is only preserved when a direct connection is desired such as with Kobayashi Masaki’s 1965 film Kwaidan.

J-Horror and Kaidan

In modern Japanese, kaidan carries a nuance of the past, of old-style Edo period ghostly tales. Few modern Japanese horror films are referred to as kaidan, but instead use the English loan word horror. The word kaidan is used conspicuously to set a tone and establish content before the first picture flickers on the screen.

Sep 18, 2010 @ 21:03:18

Found your link from Obakemono Forum site. I go by “Gamerprinter” there.

I am currently in the process of developing a roleplaying game setting based on feudal Japan crossed with Asian Horror, called Kaidan. A kind of D&D game experience set in a history more similar to the events at the end of the Genpei War, with an altered history and different location, but otherwise a fantasy Japan setting rich with yokai, oni, kami and yurei – your various articles have proven interesting indeed.

My first product is a 3 part adventure, the first one features a Haunted Ryokan story. The second part features an Onryo daimyo, a hebi-onna, and a village of hengeyokai. While the third adventure involves performing a rite to free a woman trapped as a yurei, and an encounter with a dai-tengu .

All influenced by several trips to Japan, a lifetime love of Koizumi Yagumo (Lafcadio Hearn’s Kwaidan), and stories shared by my relatives in Japan.

Thanks for sharing your tales!

Michael

Oct 23, 2010 @ 05:40:12

i like story about ancient Japan

thanks for the translate so i can understand about the story

Mar 27, 2013 @ 20:03:42

Michael,

I want to play it. o.o

Aug 01, 2013 @ 17:41:11

First of all, thank you for putting together so many good resources! Living so close to Sakaiminato and keeping a blog about this region, I feel I should be posted more kaidan, but any work I do on the topic feels very unsatisfactory because it such a broad topic to grasp. I hope you don’t mind if I reblog your posts sometimes.

Just to flesh out the kaidan .vs. kwaidan bit, the semi-official stance is that “kw” was Hearn’s attempt to capture the Izumo dialect:

“A large part of the work that went into KWAIDAN, was listening to and putting to use the stories Setsu (Hearn’s wife) told him. He himself recognised how important a role she played in the books’ creation, praising her as “the best wife in the world”, remembering to honour her for her contribution. The extent to which Hearn valued Setsu’s storytelling, (even more than lexical meaning), is evident in the title KWAIDAN itself. Rather than translating and replacing kwaidan with ‘ghost stories’ etc, Hearn retained the Japanese, in Setsu’s direct pronunciation of her local Izumo dialect. We are also hoping that this exhibition will draw attention to Setsu role, and thus provide impetus for the re-evaluation of Matsue’s very own talented storyteller.”

Source: http://www.matsue-tourism.or.jp/yakumo/kwaidan_exhibition/

Oct 11, 2013 @ 09:47:52

THANK YOU BURI-CHAN

May 13, 2014 @ 20:16:29

Je pense que ce poste va aller sur mon site internet

May 25, 2014 @ 15:10:37

So Kaidan is kind of like ‘stories of interesting or weird things”?, Even in western culture, this kind of topic can be funny, sad, make you wonder, or possibly even creep you out. It seems kind of like us saying ‘You will never believe what happened to me today!”

Nov 12, 2015 @ 16:15:36

I love learning about different tales about Japan.