Translated and Sourced from Mizuki Shigeru’s Mujyara and Japanese Wikipedia

You can still see turtle restaurants in Japan today offering a full-course suppon meal, including a glass of blood served with sake. But they are much rarer today than they were during the Edo period. A few strange stories come down to us from those times about ghostly goings-on in the turtle shops. This is one of them.

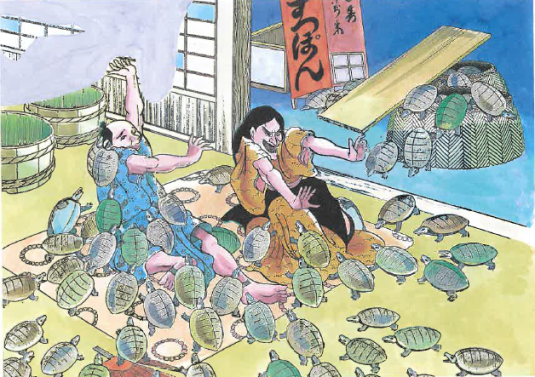

A man named Kiroku had a successful suppon shop in Nigata city. Every day he butchered and served up hundreds of turtles. One day at work, his body suddenly felt heavy. At the same time, everything became cold and dark, and it felt like he was being submerged under water. He tried to shout, but no voice came out. He felt around with his hands, and felt something even colder. It was a turtle shell. All around him were hundreds of turtles, crawling over his body and dragging him down.

Finally, Kiroku managed to let out a cry of horror, which brought his wife running into the room. When she opened the door, all of the turtles vanished.

This happened night after night, until finally Kiroku had enough. He had learned his lesson, and swore an oath against the taking of life. The wrathful turtle ghosts never came again.

Translator’s Note:

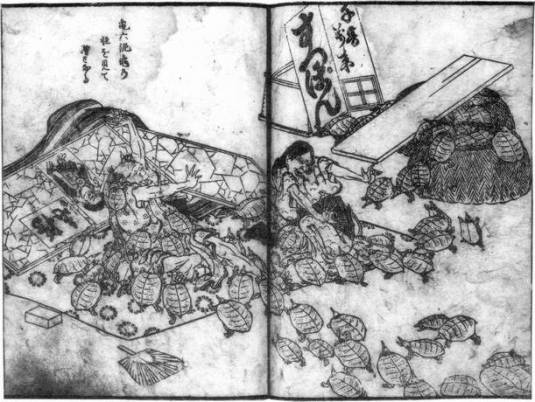

The second story of the dangers of overindulgence of suppon and ghostly revenge for Thanksgiving. This tale comes from the Edo period kaidan-shu Hokuetsu Kidan (北越奇談; Strange Stories from Hokuetsu), where it was illustrated by the famous artist Katsushika Hokusai.

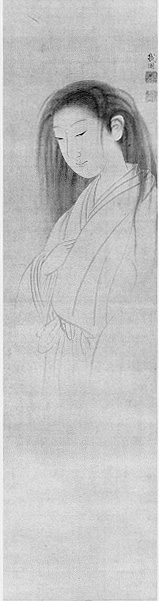

The original story was called Suppon no Kaii, which used the term怪異 (Kaii; strangeness). Mizuki changed it to the term onryo (怨霊), which refers specifically to a grudge-bearing spirit. The word is used almost exclusively for the yurei of human beings, so it is a bit odd seeing it used in the context of these turtles who are angry at being eaten. But it just goes to show the flexibility of folklore.

Mizuki Shigeru adds a footnote to this story, saying that living things must consume other living things in order to stay alive—that is the very nature of life. Even the turtles in this story needed to kill in order to live, so logically they object to the gluttony of so many of them being eaten, not the very fact they were eaten at all. Go ahead and eat turtles, Mizuki says, just appreciate their sacrifice and don’t eat too many!

Further Reading:

For more tales of magical turtles and over-eating yokai, check out:

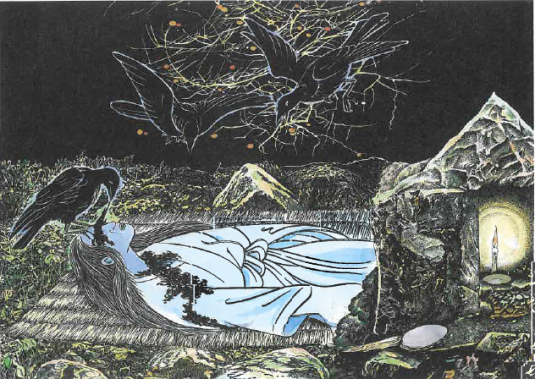

Suppon no Yurei – The Turtle Ghost

Recent Comments