Translated from Asahi News

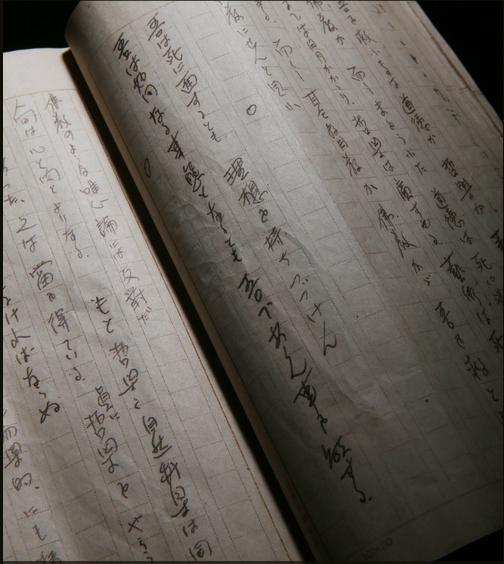

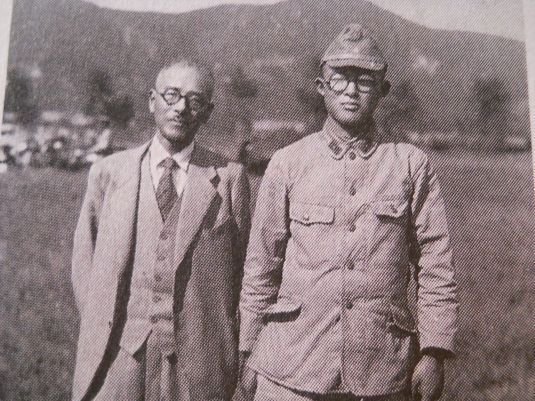

93-year old Shigeru Mizuki—famous artist of manga such as Gegege no Kitaro—recently discovered notes he wrote 73 years earlier before he was shipped off to fight in WWII. The notes are written on 38 pages of Japanese paper. In it, the 20-year old Mizuki writes of his fear of death. He attempts to overcome his fear with philosophy and religion, and to make some sense of his impending death.

Mizuki wrote:

“In order to understand who you are, you must be free of egotism, to see yourself as you truly are. You can be of no use to others when you, yourself, are corrupt. That is one of Nietzsche’s great lessons. Whenever I read that I am filled with admiration. I owe him greatly. My purpose is that if I read these words over and over again, eventually I will internalize them and become the type of person they embody.”

And:

“50-100,000 men are dying in this war every day. Of what point are the arts? Of what point is religion? We aren’t even permitted to contemplate these things. To be a painter or a philosopher or a scholar of letters; all that is needed are laborers. This is an age painted with the earth tones of graveyards. An age of buried humanity, where people are just lumps under the earth. I sometimes think being alive at this time is the only thing worse than death. Everything of worth has been discarded. What remains is violence; political authority; that’s what kills us. I have no more capacity for tears. My only relief is to lose myself in music, in painting. I turn pale at the thought of war, but that’s how I win.” (October 6th, 1942)

And

“I learn morality through philosophy, through art, and religion like Buddhism and Christianity. But nothing strengthens me to face my own death. The philosophy is too wide.”

The booklet was found by Mizuki’s eldest daughter Haraguchi Naoko when she was going through some of her father’s old papers in his office in Chofu, Tokyo. She said “Reading it was like reading my father’s mind, as he screamed against his fate. I could understand his feelings perfectly. I was overwhelmed.”

The essays have no titles. The dates are inconsistent and not always labeled. Examining the document, it looks like they were written in 1942, between October-November over the period of a month. At the time Mizuki attended school at night. He was drafted into the army the following spring. Mizuki endured fierce fighting on the island of Rabaul in Papa New Guinea, where he lost his arm in a bombing raid.

Translator’s Note:

The discovery of this note has a beautiful serendipity to it, considering I have just finished putting the final touches on my translation of the final volume in Shigeru Mizuki’s epic autobiography/history Showa: A History of Japan. It reminds me of one of the final pages in the 4th volume, where a desperate Mizuki turns towards the reader and pleads across the years:

“Never forget it was real! This actually happened to us!”

As years pass and people die—like my own grandparents, long since gone—it is easy to see stories like this as just stories. For many, WWII has no more reality than the 300 Spartans and the Battle of Thermopylae. They both make for great movies, but little else. Living links like Mizuki forestall this passage of history into legend, all the more so because he is an artist able to record and transmit his personal testament across the years. Like Will Eisner and his comic Last Days in Vietnam, Mizuki forces people to confront some of the humanity of war they might rather not think about—like having to poop on a faraway island where going outside makes you a target for enemy attack.

This note puts another human face on Mizuki’s trials. Peeking inside his head across 70 years you see a different person than the lazy layabout he portrays in his comic. I can’t imagine the darkness of being 20 years old, a soul full of art, and seeing nothing before you but a grave. Well, maybe I can imagine it a little bit—that’s the power of Mizuki’s creation. He lets us in.

I am again thankful that Showa: A History of Japan was translated into English while Mizuki is still alive. We have a tendency to wait until people are dead to honor them. Not only translated, but every volume of Showa has been nominated for the prestigious Eisner Award. I’m hoping the final volume keeps up the tradition (and maybe even wins).

The West has been the last to discover Mizuki—he wrote this comic 20 years ago and it was long ago translated into Spanish, French, Italian, and Chinese … pretty much every major language but English. I’m not sure what that says about us, if it says anything at all. Tastes are different; times are different. Translating Showa has been a personal project for me, something that truly changed my life. It’s amazing how much has happened since I wrote Drawn and Quarterly that blind email so many years ago. I am actually thankful that no one else took on the task over the past twenty years.

I sometimes feel Mizuki was waiting for me to come along …

And if you’ve never read it, I highly recommend you check out Shigeru Mizuki’s Showa: A History of Japan. It’s a great comic.

Showa 1926-1939: A History of Japan

Showa 1939-1944: A History of Japan

Recent Comments