Sourced and translated from Kaii Yokai Densho Database, Japanese Wikipedia, Yokai Jiten, Nihon Kokugo Dai-ten, and Other Sources

Out on the seas comes upon a strange vision. A three-legged half-fish person rises from the water and speaks a prediction; this year shall bring a great wealth of crops followed by a devastating plague. However, the fish creature says, show my picture to anyone stricken down by the disease and they shall be healed.

Amabie are one of several prophetic yokai. The follow the same basic pattern as modern chain emails, warning that horrific things will happen if their image is not shared widely. This causes people to replicate the image and share them with as many people as possible.

The legend of the amabie arose during the Edo period and has been all but forgotten over the years until a resurgence during the Covid pandemic of 2020.

What does Amabie mean?

The word Amabie (アマビエ) is written entirely in katakana, giving no clue as to its meaning. “Ama” phonetically can mean nun (尼), female diver (海女), or fisherman (海士). “Bie” in the Higo dialect is related to fish. Therefore amabie most likely refers to some sort of merfolk.

The History of Amabie

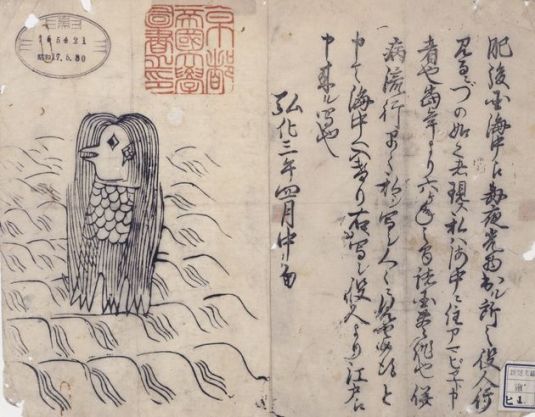

There is only one single account of an Amabie. It appeared in the Edo period, in the third month of the 3rd year of Koka (mid-May, 1846 by modern calendars), in Higo province, modern day Kumamoto period. Locals reported a strange, glowing light appearing in the sea each night. Finally a government official was sent out on a boat to investigate.

When they arrived at the glow, a strange creature appeared. It spoke, saying “I am an Amabie, who lives in the sea. For six years hence crops will be abundant across all provinces. But a horrible plague shall spread. For those who succumb, show them my image as soon as possible and they will be cured.” With that said, the creature sank back into the sea.

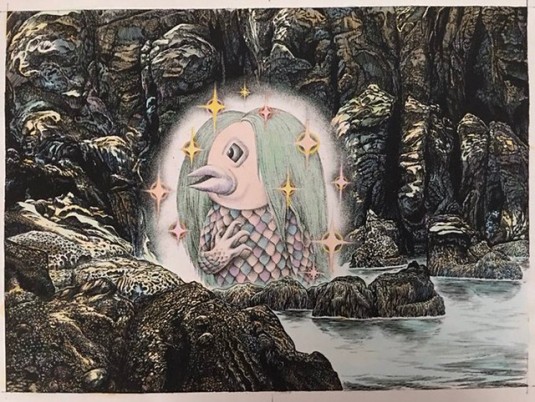

The official drew an illustration of what he saw, showing a chimeric creature with a bird’s beak, fish scales, long hair, and three finned feet. The story and illustration were printed in kawaraban woodblock-printed broadsides and disseminated across Japan.

Mermaid Legends and Pandemics

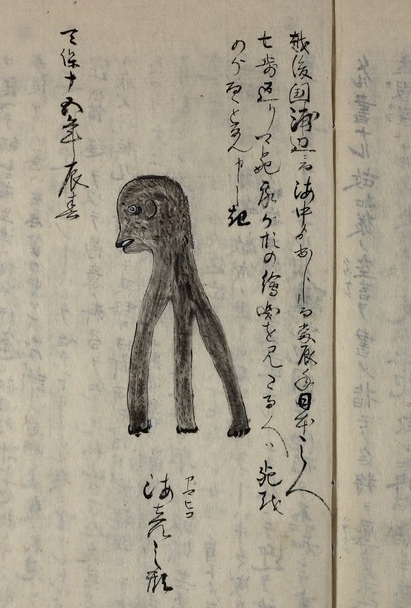

The amabie is not the first magical mermaid to appear in Japan. In Tensho 9 (1581), Tokugawa vassal Matsudaira Ieda drew this illustration in his diary and wrote that a mermaid had appeared in a dried rice field on New Year’s Day in Azuchi. It was more than six feet tall, and ate several people.

The year before Ieda’s illustration Japan had suffered heavy rains and flooding, followed by a pandemic that killed many across the country. Temples were filled with people praying for an end to the pandemic.

Using yokai as amulets of protection against disease was a common tradition in Japan, usually images of oni that were meant to frighten off epidemics. There is some evidence of mermaid prayer amulets being used at the time.

Amabie Variations

While the Amabie is the best known, there are many variations on the same story, some of them older. It has been suggested that the Amabie is a misheard or mistranscribed versions of earlier stories, mixed with mermaid legends.

Folklorist Yamato Koichi identified seven variations of amabie. Nagano Eishun later expanded this to nine. While their physical forms are different, most share similar stories offering predictions of both a bumper crop followed by plague, and the mitigation of showing pictures of their image.

Here are some of them:

Amabiko (海彦; 海 (ama, sea) + 彦 (hiko, boy).

The earliest version with an exact age appeared in Echigo province, now Nigata prefecture, in Tempo 15 (1844). The kawaraban “Tsubokawamoto.” The illustration shows a creature with three legs growing out of its head, with no body. The accompanying text says this creature prophesied that 70% of Japan would die that year if not shown this image.

Amabiko (尼彦; 尼 (ama, nun) + 彦 (hiko, boy)

The text states that in Meiji 15 (1852), a person named Hikozaemon Shibata heard a monkey’s voice every night, and eventually tracked it down to the source. He encountered the Amabito who delivered the usual dire warning.

The veracity of this account is dubious, as it says it took place in “Shinji town,” which does not exist, and uses the name Kumamoto prefecture instead of Higo province, showing that it was created after the abolition of the feudal clan system in 1871.

Amabiko Nyudo (尼彦; 尼 (ama, nun) + 彦 (hiko, boy) + 入道 (nyudo, priest)

This variation comes from Hyuga provice (Miyazaki prefecture). It tells the same account as the other Amabiko but with a different image.

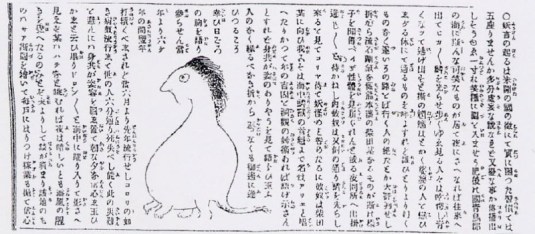

Amahiko no Mikoto (天日子尊; Amahiko, sunlight + Mikoto, noble child)

This version comes from Yuwaza in Nigata prefecture, and appeared in the Tokyo Nichi-Nichi newspaper in Meiji 8 (1875). This version was said to have appeared in a rice field. The illustration shows something like a four-legged version of a daruma doll. This version carries the name of “mikoto” identifying it as something holy, and it professed to be a servitor of the heavenly gods.

Arie (アリエ)

In 1876, the Yamanishi Nichi-Nichi newspaper reported a similar version of the tale, with a different version of the creature under the name of Arie. It was said to have come out of the ocean in Kumamoto and made its prediction. As many of the details were incorrect, this was declared a hoax at the time.

Why all of these Amabie?

No one really knows what sparked the proliferation of amabie stories at the time. Speculation is that the stories of disaster and salvation played on people’s fears and made for a good sales pitch for the kawaraban broadsides. As there was little contact between towns at the time, they would have been unaware of the other variations of the legend. Enterprising traveling salesmen could have encountered the stories and then concocted their own legends.

There was no pandemic in the 1840s, although cholera would reach Japan in the 1850s, and the third bubonic plague pandemic would strike in 1896. However, the fear of disease was constant and many households would have not wanted to take the risk by not buying a picture of the amabie when offered.

The modern resurgence of amabie was sparked on March 6th, 2020, when the Kyoto University Library Twitter account posed an image of the 1846 illustration with an account of the manifestation. On March 17th, the family of Shigeru Mizuki posted his version of the yokai as well to pass on its blessing. From there, Japan’s artists’ imagination was sparked and images of of the healing yokai began to spread across the internet.

Translator’s Note:

Well, it has been three years since I have posted anything new on this site! I started this when I was an amateur, and since it lead to professional work and writing my own books and lecturing I really didn’t have time to maintain this site as a hobby.

But it seemed like this was the time to come back and make another post! May the spirit of the Amabie live on and help us all out in these troubled times!

I rarely visit this site anymore, but anyone who wants to see what I am up to can find me at https://zackdavisson.com/

Apr 03, 2020 @ 02:21:37

Thanks for this update! We have several of your books (thank you Powells) and follow a few other series scholars.

Have you done any work concerning the ghosts of the 2011 tsunami? I found a single reference in a UK article about a buddhist priest who was trying to help.. he ended up building a mobile tea truck and “bringing the temple to the people” to help them “exorcise” or release the ghosts…

Best regards

Apr 03, 2020 @ 08:33:23

Welcome back! You were missed. I have several of your books and enjoy them. Thank you for your posting in this time of great stress.

Apr 03, 2020 @ 11:24:05

Thank you for passing on this account and the miraculous images that will help us with the coronavirus. You might add that Amabie is a character in the fifth anime series based on Mizuki’s manga, the one in which she is one of the chosen 47 Yōkai Warriors (one from each Japanese prefecture) are identified. She is #9, representing Kumamoto. There is a page devoted to her in the Gegege no Kitarō Fandom wiki:

https://gegegenokitaro.fandom.com/wiki/Amabie

And I’m lucky enough to have an animator’s sketch of her in my gallery of original art from the fifth anime series:

http://sensei.rubberslug.com/gallery/inv_info.asp?ItemID=270448

May all these images keep you and all of us Yōkaiphiles safe and healthy.

Apr 03, 2020 @ 17:24:08

I was hoping you would come back! Thank you.