Translated from Opinions About Life and Death as Told by the Legend of Yaobikuni, Japanese Wikipedia, and this Blog

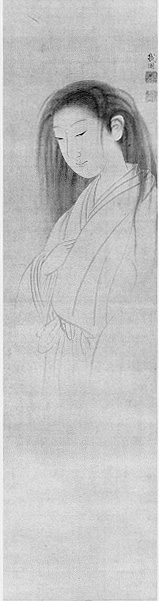

To learn more about Japanese Ghosts, check out my book Yurei: The Japanese Ghost

Japan has mermaids, but they are very different creatures from western folklore. They can take many shapes, but the most common in the form of a fish with a woman’s head. And even then, appearance is not their most distinctive feature—eating the flesh of a mermaid is said to grant an extended lifespan. And sometimes it does something else.

Yaobikuni – The Eight-Hundred Year Nun

One of Japan’s most famous folk legends, variations of this story can be found across the entire country. Most versions of the story involve a fisherman who catches a strange fish. He brings it home to cook for his family and a friend. The friend notices that the fish has a human face, and advises them not to eat it. The fisherman throws the fish away, but his hungry daughter slips into the kitchen and eats it any way. Cursed with immortality, she becomes known as Yaobikuni—the eight-hundred year nun.

Here is an interesting variation translated from Takeshi Noji’s “Opinions About Life and Death as Told by the Legend of Yaobikuni” [八百比丘尼伝承の死生観]. Notice the difference about how the mermaid flesh is discovered.

One day a man was invited to dine and be entertained at the house of another man whom he had never met before. Now, this was a man learned in Buddhism and who had attended many lectures, and he knew that many such invitations lead to places such as the Palace of the Dragon King or to a dead man’s abode. He accepted, but was on his guard.

When the feast came, he saw that he was being served mermaid meat. He was repulsed by the feast and did not eat it, but slipped some of the mermaid meat in his pocket as a souvenir of his strange adventure. Unfortunately, when he came home that night his daughter searched his pockets to see if her father had brought her a treat, and gobbled down the mermaid meat. From that time on she did not age.

Her life become one of bitter loneliness. She married several times, but her husbands aged and died while she went on. All of her friends and loved ones died as well. Eventually she became a nun, and left her village to wander the country. At ever place she visited, she planted a tree—either cedar, camellia, or pine. She eventually settled at Obama village in Wakasa province (Modern day Fukui prefecture) where she planted her final set of trees. The trees still stand to this day, and are said to be 800 years old.

Three Cedars of Togakushi

Normally, mermaid legends are found on port towns bordering the sea. But this story comes from Togakushi of Nagano, approximately 65km away from the shore. This legend follows the same beginning as the well-known Yaobikuni legend, but adds it’s own cruel twist.

One day, a fisherman caught a mermaid in the ocean. The poor creature begged for it’s life, but the fisherman didn’t listen and killed it. He brought the meat home to where he lived with his family and three children.

The following day, when he was out fishing, his hungry children crept into the storage box in the kitchen and gorged themselves on the mermaid flesh. Soon after their bodies began to change. Their skin sprouted scales like that of a fish. At the end of their torment, they died. The father was wracked with grief, and bitterly regretted his actions. But it was too late.

In a dream, a divine messenger told him “To save your children’s souls, make a pilgrimage to Togakushi, and plant three cedar trees to honor them.” The father did as he was told, and travelled the 400km to Togakushi to plant the trees.

They trees are still there, called the Sanbonsugi of Togakushi (Three Cedars of Togakushi) where they are worshipped in a Shinto shrine.

Translator’s Note:

I came across this blog post on the Three Cedars of Togakushi, and thought it was an interesting legend to post about! However, you can’t really put the Togakushi legend into context without the much-more famous story of Yaobikuni, so there they both are!

I like the variation of Yaobikuni that I found. Like the legend of Okiku, there are hundreds of different versions of her story spread all across Japan, each one changed in just a few key details. This one features a wily man who is too smart to fall under a spirit’s spell, but is then undone by his own daughter.

Recent Comments