If you are walking through the forest and hear mysterious laughter or the sound of crashing trees, take caution. You may have stumbled into the territory of the species of tengu called guhin. These mischievous spirits are charged by the mountain kami with the task of ensuring humans have proper awe and dread of their craggy realms.

What does Guhin mean?

Guhin is made up of two kanji. 狗 (gu) meaning “dog” and 賓 (in) meaning “guest” or “visitor from afar.” These seem innocuous enough, however both have deeper associations.

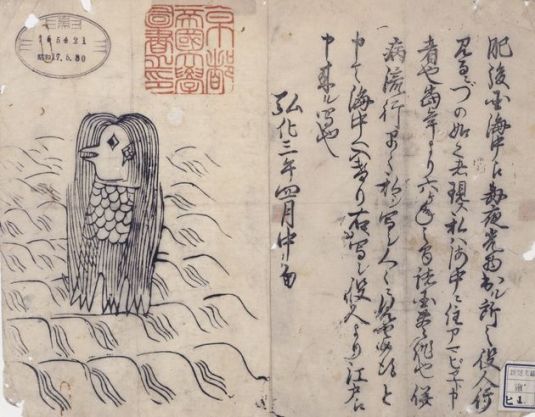

狗 is the kanji used in the name tengu (天狗), which translates literally as “heavenly dog.” Tengu originally take their name from the Chinese tiangou, a black dog of the heavens that eats the moon during eclipses. Japan took the name of the tiangou and attached it to the garuda avian deities from India to create what we know of as the Japanese tengu.

賓 can also be read as marebito, and refers to an ancient belief in divine beings who come from afar to bring supernatural gifts of wisdom and knowledge. In ancient Japan, villages welcomed marebito with rituals and festivals.

Guhin the Dog Tengu

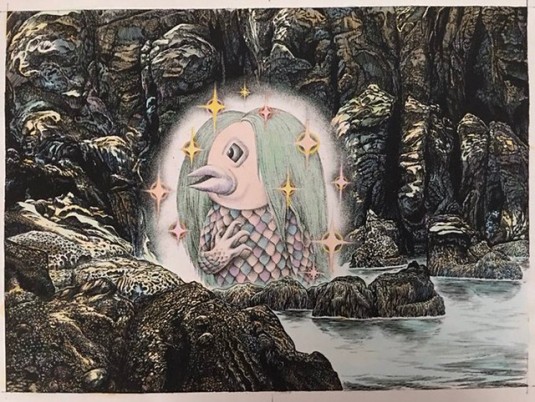

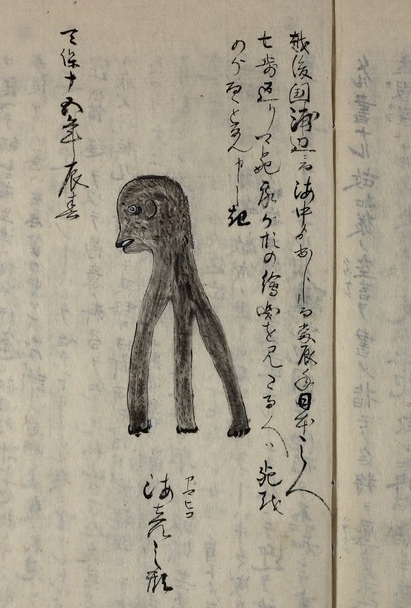

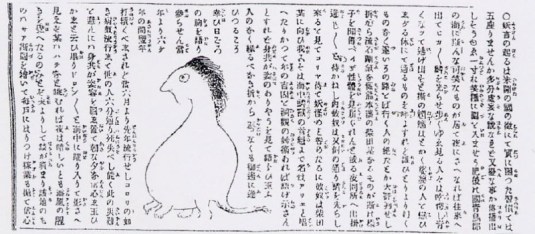

In modern times guhin are usually depicted as dog-headed creatures, as opposed to the usual avian ko-tengu or long-nosed dai-tengu. However, this appears to be a modern invention. There are no physical descriptions of guhin in Edo period sources, where the guhin always manifest as mysterious forces in the woods and are never actually seen.

I’ve not been able to find where the image of guhin as dog creatures come from, and the oldest description I can find with that description comes from the 1969 English-language Encyclopedia of Beasts and Monsters in Myth, Legend and Folklore. The anthropomorphic wolf description of guhin is more common in English language sources and does not appear often in Japanese.

Guhin as Regional Variant of Tengu

Guhin are not considered an individual tengu species everywhere. In many parts of Japan the word is used as regional variant of tengu. In Aichi and Okayama prefectures, and the Kotohira district of Kagawa prefecture, guhin is simply the local term for tengu.

The Legend of Guhin

Guhin are considered the lowest order of tengu. They are common tricksters, far removed from the lofty reams of the dai-tengu and ko-tengu. It is said that while the dai-tengu and ko-tengu occupy the sacred peaks of Japan, the guhin live in the myriad nameless hills and mountains that define the craggy surface of a country that is 80% mountainous. Also, while dai-tengu and ko-tengu are associated with Buddhism and the mountain aesthetic religion of Shugendo, guhin are closely identified with traditional sangakushigo mountain worship and the ancient folkloric deities that were native to Japan before the introduction of Buddhism from Korea.

Guhin are, to borrow from Shakespeare, but deities of the working day. Their existence is intimately intertwined with human lives, and they exist on the earthy not heavenly planes. They are said to be servants of the mountain kami, and their primary task is to inspire in humans proper fear and awe of the mountain realms. Guhin are said to be the cause behind such mischief as tengu taoshi, an auditory phenomenon where you hear the crashing of a tree falling when no tree actually fell, tengu tsubute, a rain of gravel thrown from nowhere, tengu warai, a mysterious laughter heard deep in the woods, and tengubi, mysterious lights that drift through the forest.

In the 1764 collection Sanshu Kidan (三州奇談),a story is told of a man who wanders deep into the mountains gathering leaves when he is assaulted with a sudden and ferocious hailstorm. The man fled back to the villages where locals told him that a guhin lives in those woods, and that anyone who took a single leaf would die.

Aside from this warning, there are no accounts of guhin causing actual harm to humans. They lack the divine powers of dai- and ko-tengu. However, they are still supernatural beings. It is said if you didn’t heed the guhin’s warnings and wantonly destroyed nature that they could still bring disaster to human families.

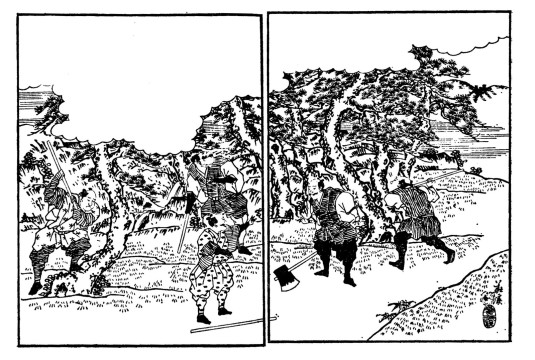

Guhin Mochi

It was important for those who worked in the mountains and woods such as loggers to maintain good relationships with guhin. They held festivals to offer them mochi rice cakes which were thought to be a favorite treat of the guhin. The 1849 Sozan Chomon Kishu (想山著聞奇集) records the custom in Mino province called Guhin Mochi, which was mochi set out in the woods to placate guhin in the mountains.In places such as Gifu and Nagano these rituals and festivals are still maintained.

Sankidai Gongen of Mt. Misen

In a reversal of most guhin legends, in the western part of Hiroshima prefecture guhin are considered instead to be the highest order of tengu. According to local legends, a guhin named Sankidai Gongen lives in Mt. Misen at Miyajima shrine. This is the primary kami of the local tengu-worshiping sect of Shingon Buddhism.

In the forests of Ujina, it was said there was a law that not a single new leave should be taken and only dead trees could be harvested.

Translator’s Note

I’m back again! This was by special request of Stan Sakai, and hey, I would do anything for Stan Sakai! Maybe we will see a guhin popping up in Usagi Yojimbo?

Recent Comments