Translated and adapted from Mizuki Shigeru’s Mujara and other sources

To learn much more about Japanese Ghosts, check out my book Yurei: The Japanese Ghost

You have a magical ball in your butt, and kappa want it.

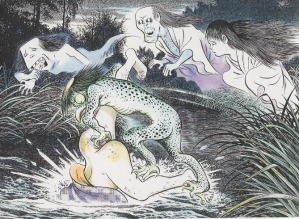

At least that is how the story goes. Although modern kappa are often portrayed as cute and mostly harmless, during the Edo period they were monsters who had a particularly vicious method of killing their victims. In probably one of the strangest bits of Japanese folklore, it is said that human beings have something in their body called a shirikodama (尻子玉), which translates literally as “small anus ball.” The ball is nestled either immediately inside the anus, or deeper inside the intestines or the stomach. The kappa have a preferred method of extraction.

Folklorist/manga artist Mizuki Shigeru wrote:

“Ever since I was a child I heard that I had to be careful in the water because the kappa would try and take my shirikodama. It was said that in the water, a kappa would come from below, extend an arm upwards and stick a hand up your anus to extract the ball.”

In some stories, the kappa don’t reach up with their hands but instead actually suck the shirikodama from the body. However it was taken, the person whose shirikodama was extracted from was almost always killed in the process. Usually the kappa would hold them underwater to drown them first, before taking the ball.

What is a Shirikodama?

No one really agrees on what the shirikodama is. Some say that it is the human soul, hardened into physical form. Some say that the shirikodama in pictures resembles the Buddhist Hojo, or wish-granting jewel. The hojo was onion-shaped, with a round body and a tapered top. The usual depiction of the shirikodama does indeed resemble this shape.

Many associate the shirikodama with the liver. Kappa were known to love human livers, and some say that the shirikodama was the liver, or that the ball was blocking access to the liver with the liver being the actual target for the kappa.

Why Do They Want It?

Again, no one really knows for sure. The most basic explanation is that kappa consider the shirikodama to be a delicious delicacy and that they eat it as soon as it is removed. This explanations is contradicted by some Edo era depictions such as the one by Jippensha Ikku that shows a kappa with a freshly extracted shirikodama holding it far away from his face and clearly disgusted with the item. The shirikodama was said to smell as bad as the anus it was removed from.

In one story, it was said that the kappa paid the shirikodama as a sort of tribute and tax to the Dragon King who lived under the sea and was the lord of all things under the water. What the Dragon King would want with such an item no one has dared to guess.

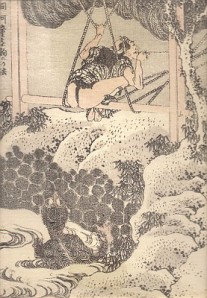

But they did want it. A humorous print by Hokusai Katsushika called “How to Fish for Kappa” (Onajiku kappa-wo tsuru no hō ; 同河童を釣るの法) shows a man using his own backside as bait to lure a kappa in to be caught with a net.

The Origin of the Shirikodama

The most commonly accepted origin is that drowning victims often have an open or extended anus, looking as if something was taken out of it. Bodies that had drowned in the river or ocean and then washed up on shore might have looked as if something had been forcibly extracted from the anus.

With kappa moving further and further way from their role as monsters in Japan, the legend of the shirikodama is on its way to being forgotten. Kappa have been recast in Japan as being friendly mascots of various companies or harmless characters on children’s cartoons. In movies like the popular “My Summer Vacation with Coo the Kappa,” the cute little kappa Coo never once sneaks up on its human friend Koichi to forcibly remove a magical ball from his anus.

Further Reading:

Check out other kappa tales from hyakumonogatari.com:

Recent Comments