Half human. Half yokai. Hanyo have become a staple character in recent yokai comics and animation. But do they have roots in Japanese folklore?

The answer to that is a pretty resounding no. Hanyo are almost exclusively the creation of modern comic book artists and animators. More specifically, hanyo are the creation of Takahashi Rumiko, and to a lesser extent Mizuki Shigeru. While half-human/half-yokai children do exist in Japanese folklore, they are—with few exceptions—normal human beings. Whatever it is that makes a yokai, it doesn’t carry over to their half-human children.

What Does Hanyo Mean?

Hanyo is a neologism invented by Takahashi Rumiko for her comic book Inyuyasha. She took the kanji Han (半; half) and put it next to Yo (妖; apparition)—alternately spelled hanyou in an attempt to imitate the Japanese long vowel sound—to create a word for her concept of half-yokai characters. Takahashi has created an entire mythology around yokai, with variations depending on if their mother or father was a yokai, and attempts to become a full-blood human or yokai.

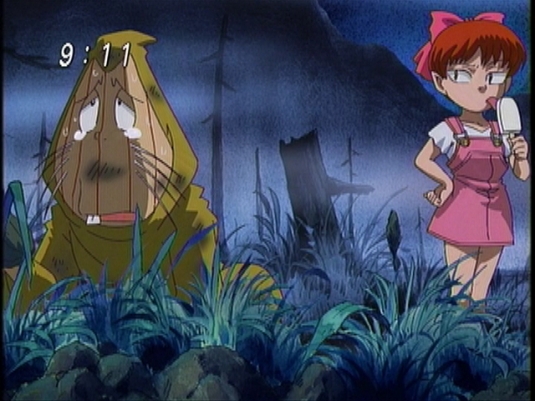

Mizuki Shigeru had earlier invented the term hanyokai (半妖怪; half-yokai) for his characters Nezumi Otoko and Neko Musume in his comic Gegege no Kitaro. In Mizuki Shigeru’s comics, the two hanyokai are in practice 100% yokai (Nezumi Otoko is over 360 years old, for example) and the term is used largely as an insult. Kitaro sometimes talks down to Nezumi Otoko for being only a hanyokai and not a true yokai. This was possibly mirroring the distaste for half-Japanese children when Gegege no Kitaro began, most of whom were the children of occupying U.S. soldiers and Japanese women.

It could also relate to Mizuki Shigeru’s theory of yokai being single-souled and humans having double-souls. Yokai being single-souled, focusing on whatever their task or motivation is—counting beans or whatever. Humans, and the other hand, were conflicted and at war with themselves. In Gegege no Kitaro, Nezumi Otoko is one of the few characters that “switches sides” between good and evil, possibly resulting from his human double-soul. But the same cannot be said for Neko Musume, who is squarely on Kitaro’s side. So this is just speculation. Maybe he just thought hanyokai sounded cool.

Half-Yokai/Half-Human in Japanese Folklore

The children of yokai and humans—and even yurei and humans—are relatively common in Japanese folklore. Almost all of these stories fall in the Magical Wife genre (I have never heard of a Magical Husband story). The stories follow a similar patter where a man performs some task/has an encounter, later a mysterious woman comes to be his wife provided he perform some condition like never speak of the previous encounter, never look in a box, etc … The couple live happily for several years, have some kids, and inevitably the husband breaks his promise and the Magical Wife leaves.

The most famous Magical Wife story is the tale of the Yuki Onna, where a snow demon comes upon two woodgatherers freezing in the forest. The Yuki Onna kills the older one, then falls in love with the younger. She eventually marries him as a human—under the condition that the husband never speak about his frozen encounter—has children and lives together many years. When the husband eventually gabs, the Yuki Onna flees, abandoning her children and spouse.

There are many, many more Magical Wife stories, like Hagoromo the Tennin and some about transformed animals and henge. There are stories where a dead woman’s yurei returns to her husband, take cares of him and bares his children, performing her wifely duties before she is able to return to the afterlife. The one thing these stories have in common is that the children from these mystical mash-ups are all normal, human children.

(The Magical Wife genre is popular in Western folktales as well, popular enough that it has its own classification under the Aarne–Thompson classification system—#402 The Animal Bride.)

The Exceptions—Kintaro and Abe no Seimei

There are always exceptions. In this case, there are two of them, although only one could really be called a hanyo or hanyokai.

Kintaro the Nature Boy is one of Japan’s most famous and popular folkloric figures. Incredibly strong even as a baby, and friends with the bears of the woods, there are multiple variations of his origins. In one of them, his mother the Princess Yaegiri became pregnant when the Red Dragon god of Mt. Ashigara sent a clap of thunder to her. This is not the most common origin for Kintaro—most stories have his mother fleeing some conflict while pregnant and giving birth in the mountains. And even then, with a Red Dragon as a father Kintaro would more properly be a hanshin, a demi-god, and not a hanyo.

Abe no Seimei is the other exception. A real person, Abe no Seimei was a famous onmyoji ying/yang sorcerer during the Heian period. He has since passed into folklore, and it is difficult to separate the fact from the legend when it comes to Abe no Seimei. One of the legends, however, is that his mother Kuzunoha was a kitsume, a magical fox.

The legend states that Abe no Yasuna came upon a hunter trapping a fox. Yasuna battled the hunter and won, and set the fox free. A beautiful woman named Kuzunoha appeared to tend his wounds, and the two fell in love and married. Their child Seimei was born, who was exceedingly bright. One day, while Kuzunoha was watching chrysanthemums, a young Seimei saw a piece of fox tail poking out from her kimono. The spell broken, Kuzunoha the fox returned to the forest, leaving her son behind but granting him a piece of her magical powers. This makes Abe no Seimei the only true hanyo in Japanese folklore.

The Children of Ubume

There is one more semi-exception. Ubume are a specialized type of yurei, who die while pregnant leading to a still-living child being born from a dead body. Ubume are ghost mothers who come back to tend for their living child, who is often trapped in a coffin buried under the earth. By some legends, the children of these ubume are special, often faster and stronger than normal humans.

The most famous ubume child is, of course, Kitaro from Gegege no Kitaro.

Translator’s Note:

I wrote this because I get asked fairly often about hanyo, mostly from fans of Inyuyasha who want to know how authentic Takahashi Rumiko’s use of Japanese folklore is. The answer is “not very.” She creates her own worlds with her own mythologies. But her creation of hanyo has proved popular enough to crop up in other comics as well, like Rise of the Nura Clan and Maiden Spirit Zakuro.

However, true human-hybrids are exceedingly rare in Japanese mythology and folklore.

Further Reading:

For more stories from Hyakumonogatari.com, check out:

Recent Comments