Translated from Konjaku Hyakki Shui, Mizuki Shigeru’s Mujara, and Japanese Wikipedia

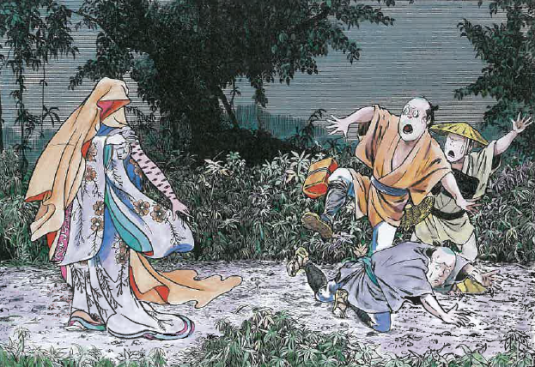

A young girl covered entirely in a tattered robe creeps up to you on a darkly lit street. A poor beggar girl, she thrusts out a hand for alms, hoping that you will take sympathy on her plight. But just as you go to reach for your wallet to drop a few coins in her hand, the lamplight flickers exactly so and you see a site that will terrify you for as long as you live. For on that outstretched arm glitter hundreds of eyeballs, blinking in the reflected lamplight.

What Does Todomeki Mean?

A tricky question! Looking straight at the kanji, todomeki means “hundreds-of-eyes demon.” That is 百々 (todo; hundreds) + 目 (me; eye) + 鬼 (ki; demon). But if you listen to the word instead of reading the kanji, then you hear some of those homophones Japanese is famous for and you realize that the name “todomeki” is a pun—at least a pun understood by those in the Edo period.

There is another reading for todome, which is鳥目, meaning “bird’s eye” (鳥 todo; bird) + (目 me; eye). This doesn’t refer to an actual bird’s eye, but more to its shape. In old Japan, coins had a round whole hole stamped through them so they could be strung together and carried on a string. Some modern Japanese coins still retain this feature, mainly 5 and 50 yen pieces. This round hole reminded people of the perfectly round shape of a bird’s eye, so “todome” became a slang term for money. Furthermore, when a person has a “bird’s eye,” it mean that they were night blind—they couldn’t see at all in the dark.

As you will see by the story, the yōkai todomeki plays off of both of these puns.

The Story of Todomeki

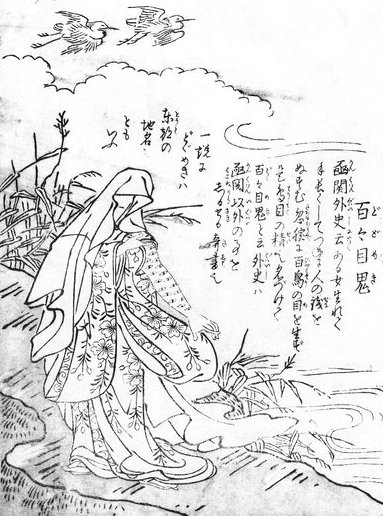

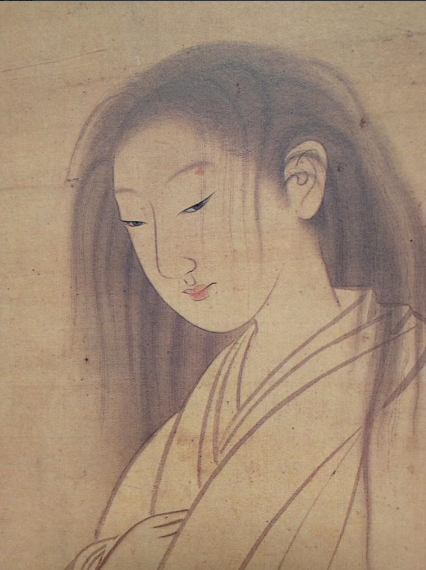

Todomeki appears only in Toriyama Sekien’s Konjaku Gazu Zoku Hakki (今昔画図続百鬼; The Illustrated One Hundred Demons from Past and Present). He tells her story thusly:

“The unofficial history of Hakkoseki tells of a young girl was born with unusually long arms. She took advantage of her natural attributes to become a thief, constantly stealing money. But the spirit of money took its own revenge, and marked her body with hundreds of bird’s eyes, one for every coin she stole. She transformed into the todomeki, a hundreds-of-eyes demon. Tales of the todomeki are told in the unofficial histories of several places. She possibly originates from Toto.”

That’s it! That’s the sum total of the legend of the todomeki!

Like Kyokotsu, Todomeki is one of Toriyama’s “pun yōkai.” Toriyama had several volumes of his popular “Illustrated One Hundred Demons” series to fill, and not nearly enough yōkai to fill them. He often invented his own yōkai, based off of half-heard legends or mélanges of Chinese folktales or just completely made up. And sometimes he just took odd turns of phrases and made puns out of them.

It’s the equivalent of creating a monster book filled with creatures like “Bird Brain” and “Slow Poke” with the creatures treated literally—in other words, like names of Pokémon characters.

This means that Todomeki has no true history or backstory. Toriyama just thought of a visual pun and then wrote a quick story to go with it.

But there is another story of a yōkai with a similar name. A much more interesting story …

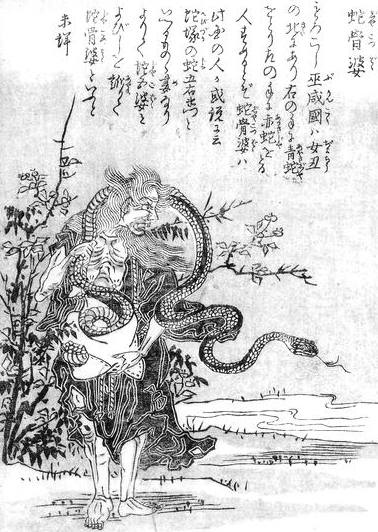

The Domeki – The Hundred-Eyed Oni

While Toriyama upped the ante by giving his todomeki “hundreds of eyes” instead of a standard-issue hundred, there are other yōkai in Japanese folklore known by the name domeki, or hundred-eye demon (or oni). These stories generally follow a set pattern of a monster doing battle with a warrior, and that monster then seeking refuge in a temple where it mends its ways and finds Buddhism. That peculiar little twist marks the stories as coming from around the Heian period, when stories of the supernatural were almost always accompanied by some tacked-on Buddhist moral that allowed them to slip by the official censors.

One of these legends comes from Tochigi prefecture. Many researchers believe that Toriyama had at least casually heard of this legend, and that accounts for the line “She possibly originates from Toto” in Toriyama’s book.

This story comes from the middle Heian period, and is set in in Hitachi province (modern day Ibaraki prefecture) and Shimosa province (modern day Chiba prefecture). Here, there was a feudal lord named Taira no Masakado who tried to set himself up as an independent emperor in what came to be known as the Masakado Rebellion. Needless to say, the current emperor and his imperial court weren’t pleased with Masakado’s behaviou, and dispatched the law enforcement officer Fujiwara no Hidesato to administer a death warrant.

Hidesato tracked Masakado across the provinces; crossing swords with him many times. However, he was unable to succeed in his mission.

At a loss, Hidesato returned to his home in Shimosa province and pleaded with the kami spirits, holding a prayer for his victory. Hidesato was granted the use of a sacred sword from the shrine, and headed off hunting again. At last he took Masakado prisoner and brought him before the imperial court for justice. For this service Hidesato was then appointed Chinjufu-shogun (Defender of the North) and awarded the governorship of Shimotsuke Province.

Now elevated in status, Fujiwara no Hidesato built a great mansion at Utsunomiya, Tochigi. One day he was hunting along the Tagen Kaido road when he passed a small village called Ouso. An old man hailed him and so Hidesato road over to hear what his subject had to say.

The old man told Hidesato that to the northwest of the village, in a town called Umasuteba, near Uta, there is an oni with a hundred eyes ravaging the land. The people of that village lived in fear, and the old man begged Hidesato to rid them of the monster.

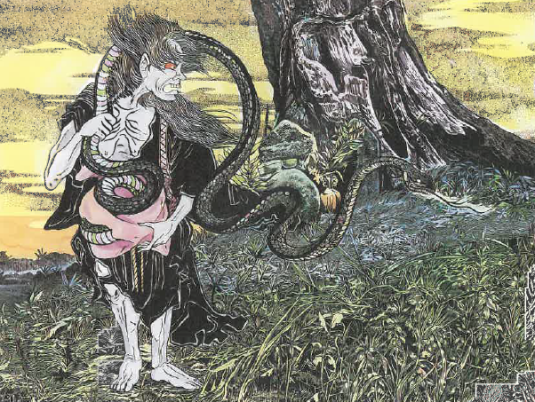

Accepting the challenge, Hidesato road to Umasuteba (another pun of sorts; “umesuteba” translates into English as the “Horse Throwing-away Place”) where he hid and laid in wait for the oni. Around midnight, the clear sky became covered with clouds and a great monster appeared. Standing 10 shaku tall, it’s hair was sharp like knives and it had a hundred blazing eyes. The monster saw Hidesato’s horse and leapt on it instantly, killing it and feasting on its flesh. Hidesato took about his bow and took aim at the distracted monster, targeting the single eye that was shining the brightest. He let loose an arrow. The arrow pierced the oni’s eye and entered into his vital organs.

Such was the power of Hidesato’s arrow that the oni was knocked backwards and flipped in a somersault, raging in pain. The demon ran away all the way to Myojin mountain where he collapsed and died. He waited till the following day to view the oni’s body, but found nothing but scorched earth and ash. Hidesato figured that molten fire must have poured from the monster’s wounds burning the corpse and surrounding area.

But the story does not end …

About 400 years passed. The Ashikaga clan took power and started the Muromachi shogunate. On the north side of Myojin mountain, in the village of Hanawada, a temple had been built called Hongan-ji. The chief abbot of that temple was the holy man Chitoku.

At that time, there was a young woman who lived at Hongan-ji. She was said to be truly virtuous and close to a living saint—she did everything right and lived the true path of Buddhism. She fooled almost everyone; except for Chitoku.

In truth, this virtuous woman was the domeki, that self-same hundred eyed oni who was thought to have died on that spot 400 years ago. The domeki hid its shape in disguise while recuperating from its wounds. And it drank blood—oceans of human blood—over those 400 years, biding its time until it was fully healed and could return to its malicious behavior.

Chitoku saw through the domeki’s illusion and revealed its true shape. Its plot uncovered, the domeki attacked the abbot and they were locked in a fierce battle. The oni’s flaming blood spurt everywhere, reducing the temple to ash. And while Chitoku engaged the oni, thrashing at it with his holy staff, he preached the truth of the Dharma. The domeki, finally hearing the words of Chitoku, dropped to its knees and begged that sutras be read for its soul. The domeki changed its ways and never caused trouble again.

The fame of this story spread, and the area became known for its carved hundred-eyed domeki masks and wooden toys.The path to Myojin mountain is stilled called the Domeki-dori(百目鬼通り).

Picture from this blog

Translator’s Note:

Another article for reader Dominique Lamssiesk. I expected to do a quick translation of todomeki as requested—easy because there is really so little to tell—and then I stumbled into the very cool tale of the Domeki. That should probably get its own entry, but I couldn’t find any pictures to go along with it, so it is getting lumped in with Todomeki. But it is still a cool story!

There is another hundred-eye yōkai, the Hyakume. That is an original creation of Shigeru Mizuki, and I might do an entry on it someday.

Recent Comments