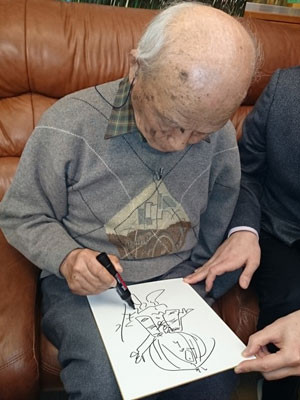

Shigeru Mizuki is 92 years old today. (A day early, I know. But March 8th falls a day earlier in Japan.) On his last birthday, he was already hailed as the world’s oldest working comic book artist. He still holds that title—just another year older.

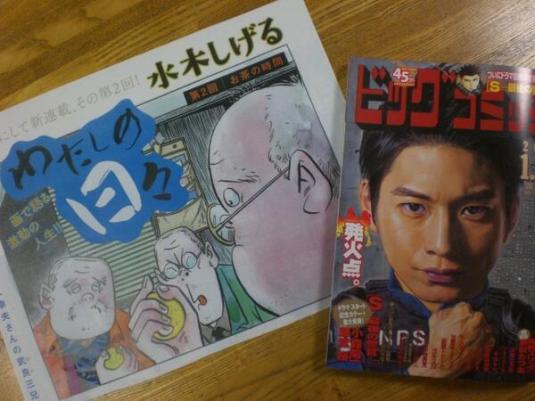

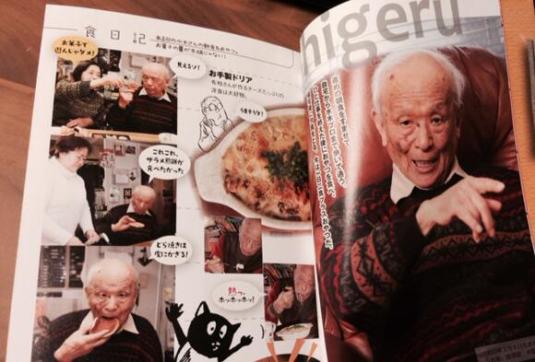

And yes, I do mean “working” comic book artist. Last year in December he announced his new comic, Watashi no Hibi (My Everyday). He also launched a new book this February touting his love of life and hamburgers and junk food called If You Go Ahead and Eat, You’ll Be Happy – The Daily Life of the Mizuki Brothers. In a recent interview, when asked if he had any doubts about taking on new work at his advanced age, Mizuki thought about it for only a brief second and replied:

“That’s something I really can’t understand. Why doubt yourself? It feels so much better to be proud—to have confidence.

I’m 91 years old, but I’m not finished yet. I’m still bursting with dreams.”

That’s beautiful.

There is no word I can think of that encapsulates Japan feels about Shigeru Mizuki other than “beloved.” He is, to the country, a sort of living Buddha; an embodiment of joy and happiness and imagination. In 2010 he was officially recognized by the Japanese government as a Person of Cultural Merit. In 2012, a TV show called Gegege no Nyobo portrayed the romantic story of how he met his wife through an arranged marriage and how they fell in love anyways.

Like Osamu Tezuka and Hayao Miyazaki, he is one of those rare individuals who shapes the fantasy dreams of an entire country. (I might even say that while Tezuka shaped Japan’s dreams of the future, Mizuki shapes its dreams of the past. And Miyazaki its present.) The only conceivable American equivalent I could conceive of might be Walt Disney when he was a living man and not a corporation. Or JRR Tolkien, if he were less academic. Or Willy Wonka if he were real.

“Come with me and you’ll see, a world of pure imagination … “

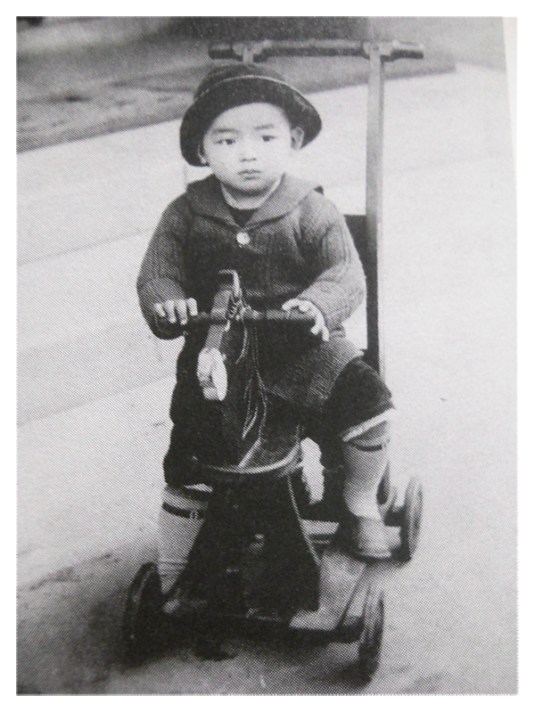

Mizuki is an artist and a scholar whose work transcends genre and medium. He was born March 8th, 1922 in a small fishing town in Tottori prefecture called Sakaiminato. From a young age he was recognized as an artistic prodigy. His work was published in local newspapers and magazines, and he had his first solo exhibition while he was still in Elementary school.

His career as a comic artist began when he returned home from WWII, his drawing arm lost to an Australian bomb while he was in a hospital suffering from malaria. (For more, see Mizuki Shigeru in Rabaul) Mizuki relearned how to draw with his left arm, and began a brief career as a kamishibai artist making paintings for the paper theater popular at the time.

He transitioned into the fledgling manga market, mostly copying Western superhero comics in his own versions of Superman and Plastic Man. And he dabbled in Western horror comics along the way. (See Mizuki Shigeru and American Horror Comics)

He didn’t have his first hit until he was in his 40s, with his horror comics Akuma-kun and Hakaba Kitaro, which later transformed into Gegege no Kitaro (published in English simply as Kitaro.) In the 1960s Mizuki helped pioneer the concept of gekiga or art manga, in the magazine Garo, transitioning comic books from children to adult readers.

In his 60s, bored with the daily grind of manga he embarked on a new career as a world folklorist. He began to seriously study the monster and folklore culture he was so fascinated with, and created a series of encyclopedias that cataloged both Japan and the world’s folklore. His work was recognized for his scholarly nature and he was invited as a member of The Japanese Society of Cultural Anthropology.

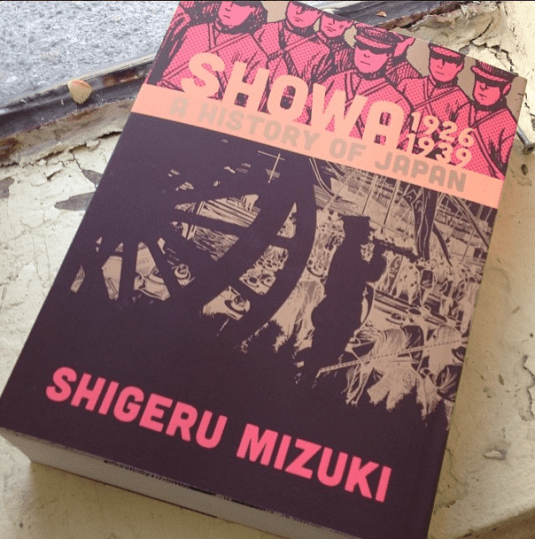

In the late 1980s, during Japan’s infamous “Bubble Era,” he was disgusted with the government of Japan attempting to cover up their wartime atrocities, and the children of Japan ignorant of their own past. Never one to play it safe, Mizuki responded with powerful works like Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths and the epic Showa: A History of Japan

. He continues to fight against right-wing militarism and government mind control, in favor of what Thomas Jefferson called The Pursuit of Happiness. Like himself, he prefers a world “bursting with dreams.”

One of the things I love so much about Shigeru Mizuki the person is that—for all his legendary status—he remains very human. He is not aloof and imperious like Hayao Miyazaki. Mizuki Shigeru posts pictures of himself chowing down on fast foods. He picks his nose. He is very much a man who inhabits a human body, and isn’t ashamed of it, and he doesn’t distance himself. But he loves life and attacks it with gusto.

It is my great privilege and pleasure to translate some of Mizuki Shigeru’s works and make them available for the English speaking world. That is a wider world than you would think. Many more people world-wide speak English than Japanese—even as a second language—and I have gotten emails from people as far away from Brazil excited to be reading Mizuki’s works for the first time.

I’ve been a fan of Mizuki’s works since I discovered them in Japan more than a decade ago, and I honestly thought they would never get English translations. They were just too weird; too … “Japanese” for lack of a better word. But now they are here, and with more to come. I am especially glad that the Western world discovered Mizuki Shigeru while he is still alive. Too often we wait until someone is dead to properly honor them.

And every time I see Mizuki Shigeru’s grinning face, I hear the whisper of Yoda coming somewhere in the background.

“When 900 years old you are, look as good you will not.”

Damn straight. Dream on, beautiful dreamer.

Further Reading:

At long last, Shigeru Mizuki’s fine works are available in English. Do yourself a favor and read them all!

Recent Comments