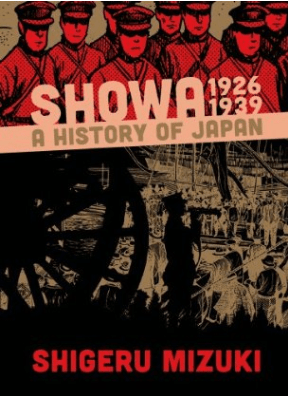

Translated and Sourced from Mizuki Shigeru’s Mujyara, Ehon Hyakumonogatari, and Japanese Wikipedia

In Kaga province (modern day Ishikawa prefecture), there lived a wealthy man known as “Salty Choji” who kept 300 head of horses. Now, these horses weren’t for riding. This man had a taste for horse flesh, and would slaughter his horses like cattle then pickle them in salt or preserve them in miso paste to get them tasting just right. Every night he tucked into a pile of salty horse meat with gusto.

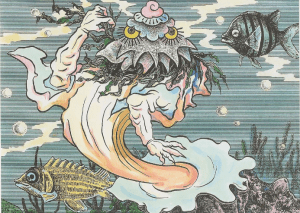

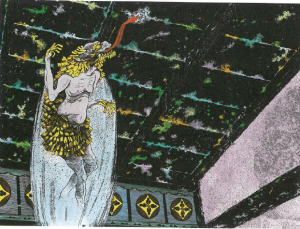

Such was the man’s appetite that Choji ate his way through 299 of his own horses, until all that was left was an ancient animal that wasn’t good for labor or food. One night Choji just couldn’t stand it any longer, and he shot the old beast anyways, then slathered it in salt and ate it down in a gluttonous frenzy. That night, however, the tables turned against Choji—the spirit of the old horse came to him in a dream and bit him on his neck.

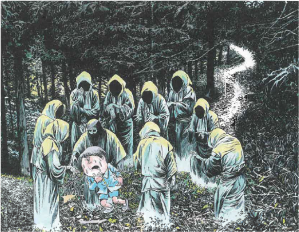

From that night on, whenever the clock stuck the hour of the time when Choji had killed the old horse, its spirit appeared and entered Choji’s body. But this wasn’t your normal possession; the horse forced his way through Choji’s mouth, and crawled straight through to his stomach. The pain was intense, and Choji felt every inch of the massive horse stretching his innards and intestinal tract. As he lay in agony night after night, Choji bitterly regretted all of his evil deeds and his ravenous appetites that lead him to this fate. But his regrets did him no good. For it was too late.

Choji summoned every manner of doctor and exorcist to aid him in his suffering. They tried everything they could but without effect. No amount of medicine or prayers for reprieve could lessen his agony. Choji’s torment continued for 100 days until at last he died. It was said his corpse was broken and shattered, like an overburdened packhorse.

Translator’s Note:

Another tale of overeating for November, and the American Thanksgiving holiday. There are a few more to come in their series! This story comes from the Edo period kaidan-shu Ehon Hyakumonogatari (絵本百物語; Picture Book of 100 Stories).

The tale of Salty Choji isn’t as strange as it seems. Although rare nowadays, horse is a standard part of Japanese cuisine, mostly eaten raw and sliced as the sashimi called basashi. I have eaten it many times. It’s delicious! So the shock of the story isn’t really what Choji was eating, but how much of it. All things in moderation is the moral of the story. That and Choji forgetting an important fact of Japanese folklore—the older an animal is, the more likely it is to have developed supernatural powers. Salty Choji should have left that old horse alone, and just gone shopping for some new ones.

The story of Shio no Choji (Salty Choji) inspired a story for the anime series Kyogoku Natsuhiko Kosetsu Hyaku Monogatari (京極夏彦 巷説百物語; Natsuhiko Kyogohe ku’s Hundred Stories), most commonly known in English as Requiem From the Darkness. I say “inspired by” instead of “adapted from” because the version of Salty Choji found in the series is VERY different from the original folktale. There is cannibalism involved, and fratricide, and all sorts of things that never appear in the simple story of Shio no Choji who could couldn’t control his appetite.

Further Reading:

For more tales of hungry yokai and yokai food, check out:

Recent Comments