Sourced and translated from Kaii Yokai Densho Database, Japanese Wikipedia, Yokai Jiten, Nihon Kokugo Dai-ten, and Other Sources

If a tree falls in the forest, and someone hears it, is that the plaintive cry of a kodama? Because that is what ancient, tree-worshipping Japanese people thought.

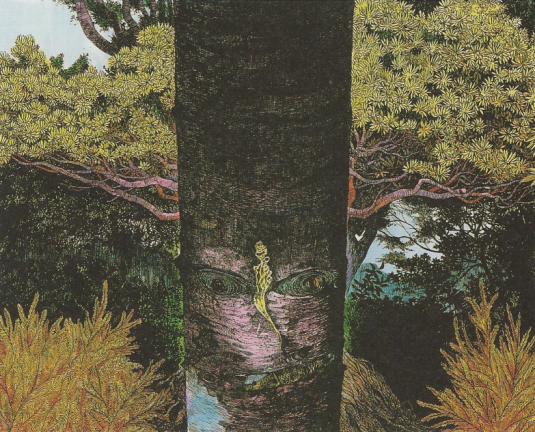

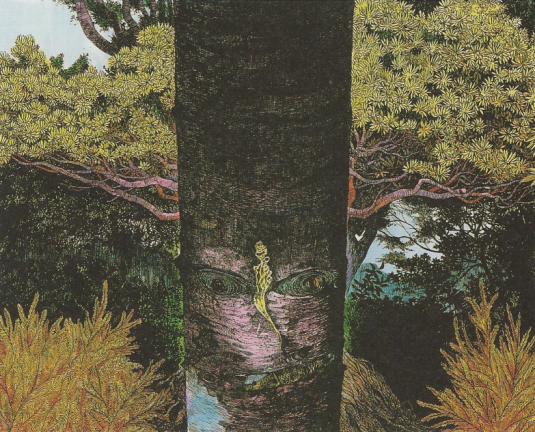

The Japanese have always known that some trees were special. For whatever reason—maybe because of an interestingly shaped trunk, or a sequence of knots resembling a human face, or just a certain sense of awe—some trees were identified as being the abodes of spirits. Depending on where you lived, these spirits went by many names. But the most common term, the one that is still used today, is kodama.

What does kodama mean?

Kodama is a very old belief, and a very old word. It was spoken long before Japan had a written language, and over the centuries there have been three different kanji used to write kodama.

The oldest, 古多万, is ambiguous to say the least. The word breaks down into 古 – (ko; old) – 多- (da; many) – 万 (ma; 10,000). Because ancient Japanese had no writing system, when the Chinese writing system was adopted kanji characters were often selected for sound rather than meaning. Unrelated symbols were jammed together to approximate the pronunciation of existing Japanese words. This is the most likely explanation for the use of 古多万.

But this combination is unsatisfying, and in later years 木魂 (木 ; ko; tree – 魂 ; dama; soul) was adopted as well as木魅(木 ; ko; tree – 魅 ; dama; soul), and now in modern times木霊 (木 ; ko; tree) – 霊 ; dama; spirit) tends to be used. There is little difference between木魂, 木魅, or 木霊, all being variations of the term “tree spirit.”

Another kanji used for kodama, 谺, also means echo. And if you read below you will find out why.

The Legends of Kodama

Along with the kanji , what exactly a kodama is has changed over the centuries, from nature gods to goblin spirits.

In ancient times, kodama were said to be kami, nature dieties that dwelled in trees. Some believed that kodama were not linked to a single tree but could move nimbly through the forest, traveling freely from tree to tree.

Still others believed that kodama were rooted like the trees themselves, or in fact looked no different from other trees in the forest. Woe betide any unwary woodsman who took an axe to what looked like a regular tree, only to draw blood as he chopped into a kodama. A kodama’s curse was something to be feared.

But they were also a sound. Echoes that reverberated through mountains and valleys were said to be kodama. The sound of a tree crashing in the woods was also said to be the plaintive cry of a kodama. (In modern times this mountain echo is associated with the yokai yamabiko and not with kodama).

Whatever form they took, kodama were said to be possessed of supernatural power, that could either be a blessing or a curse. Kodama that were properly worshipped and honored would protect houses and villages. Kodama that were mistreated or disrespected brought down powerful curses.

The History of Kodama

The first known mention of tree spirits is in Japan’s oldest known book, the Kojiki (Record of Thing’s Past) that talks about the tree god Wakunochi-no-kami, second born of the godling brood of Izanagi and Izanami.

The oldest, specific known use of the term kodama comes from the Heian period, in the book Wamuryorui Jyusho (和名類聚抄; Japanese Names for Things; written 931 – 938 CE). Wamuryorui Jyusho was a dictionary showing the appropriate kanji for Japanese words, and listed古多万 as the Japanese word for spirits of the trees. Another Heian era book, Genji Monogatari (源氏物語; The Tale of Genji), uses木魂 to describe kodama as sort of tree-dwelling goblin. Genji Monogatari also uses the phrase “either oni or kami or kitsune or kodama,” showing that these four spirits were thought to be separate entities.

Around the Edo period, kodama lost their rank as gods of the forest and were included as just one of Japan’s ubiquitous yokai. Kodama became humanized as well—there are stories of kodama falling in love with humans and taking human shape in order to marry their beloved.

Kodama Across Japan

In Aogashima, Izu Islands, people place small shrines at the base of cryptomeria (Japanese cedar) trees and still worship and pray to them. This is said to be the remainders of a nature-worshiping religion that once dominated.

In Mitsune village, in Hachijō-jima, they still have a festival every year giving thanks and respect to “kidama-san” or “kodama-san,” hoping for forgiveness and blessing when they cut down trees for the logging industry.

In Okinawa, they call the tree spirit kinushi. At night, if you hear the sound of a falling tree it is said to be the cry of a kinushi, and Okinawa’s tree-dwelling famous yokai kijimuna is thought to be a descendant of these ancient kinushi tree spirits.

Appearance of Kodama

No one really agrees what kodama look like. In ancient legends they are either invisible or indistinguishable from regular trees. Toriyama Sekian, who has set the standard for the appearance of many creatures of Japanese folklore, drew kodama as an ancient man or woman standing near a tree in his famous Gazu Hyakki Yagyō (画図百鬼夜行; The Illustrated Night Parade of a Hundred Demons).

Miyazaki Hayao used kodama extensively in his film Mononoke Hime (Princess Mononoke) and illustrated kodama as dual-color bobble-heads. Modern interpretations are wildly various, showing kodama as human young and old, or small nature sprites borrowing from European pagan traditions, or just cute animated characters.

Clearly, they are open for interpretation.

Kodama: The Game

This version of kodama comes from a Kodama game being developed by Dan Tsukasa, that I am helping out with as “yokai advisor.”

Here is Dan’s blurb for the game:

——————————————————-

Kodama is a game set in Japan during the time of Yokai. A nameless Kodama journeys across Japan to find his fellow Kodama and return them to the forest in order to protect it from a powerful Yokai. During his travels Kodama must use his abilities as a tree spirit to overcome countless obstacles, using nothing but the elements around him, he must traverse dangerous swamps, caverns and even Jigoku itself in order to protect the Kodama Forest. Kodama is able to use the world around him to his advantage, using his unique tree spirit abilities he is able to float on a breeze, grow to reach new heights and perform other abilities only known to a Kodama.

Kodama is a puzzle platformer with a few unique twists & a never before seen system known as the ‘Mori System’, the game features over 30 unique Yokai, 12 different locations and a wealth of information concerning the featuring Yokai themselves.

If I had to describe the ‘feeling’ of Kodama in a few short words, I’d say it was more of a ‘stop, smell the roses and take in the magnificent view’ type of game.

——————————————————-

You can find out more about the very cook Kodama game (along with some stunning art) at the Kodama Devlog.

Translator’s Note:

Kodama is the latest in my magical tree series of translations. Kodama are slightly different from my previous translation Ki no Kami, in that they are mostly considered to be lower-level tree spirits that actual gods. The Ki no Kami come down from heaven to inhabit the trees, whereas the kodama are the spirits of the trees themselves. And then there are the moidon, which are awakened trees with a soul like any human.

Thanks to Miyazaki, kodama are well-known in Japan (unlike some of the obscure folklore on familiar to true yokai lovers), although most would associate kodama with the white bobble-head from Mononoke Hime.

Further Reading:

For more magical tree stories, check out:

Ki no Kami – The God in the Tree

Moidon – The Lords of the Forest

Jinmenju – The Human Face Tree

Enju no Jashin – The Evil God in the Pagoda Tree

Ochiba Naki Shii – The Chinkapin Tree of Unfallen Leaves

Translator’s Note:

Recent Comments