There is nothing sad about the death of Mizuki Shigeru. And I say this as someone who shed more than a few tears when I heard the news last night. He lived about as good a life that could possibly be lived; the ripe old age of 93; wealthy in every way that matters; respected by his peers; beloved. He died a good death. The only thing that is sad is that the rest of us now have to live in a world that doesn’t have Mizuki Shigeru. And we are poorer for it.

To say that Mizuki Shigeru was a comic artist is like saying the Brothers Grimm crafted a quaint book of fairy stories or that Walt Disney made some cartoons. Mizuki was one of those rare human beings who unequivocally changed the world with his art. Without Mizuki the world—and especially Japan—would be a very different place. There would be no Pokémon, no Spirited Away or Princess Mononoke. His presence is so ubiquitous as to be almost unnoticeable. The way Mizuki saw the world has become the world. He saved the spirits and magic he loved from the darkness and gave them a new home.

He was a visionary. A philosopher. A radical. A bon viviant of the mundane. Mizuki relished the simple, sheer joy of being alive. As someone who knew the actual soul destroying pains of hunger and the terror of hanging from a cliff by your fingertips while hiding from an enemy patrol, a cheap hamburger in a full belly brought him more delight than the most expensive piece of handcrafted sushi. He believed in taking it easy, in enjoying life, and often scoffed at manga artists like Osamu Tezuka and Fujiko F Fujio who prided themselves on their hard work and long hours. They’re all dead, he would say, but I’m still here.

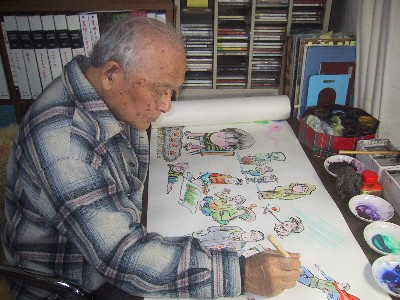

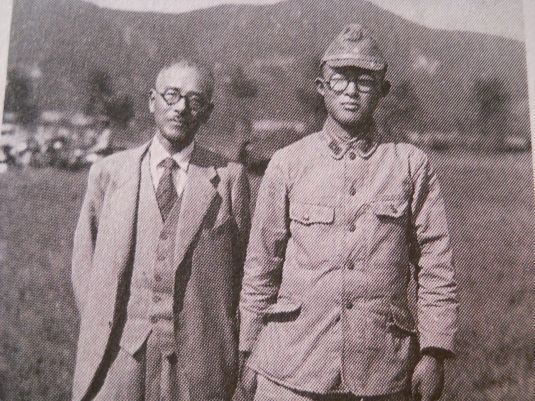

Of course, he was a comic artist, and one of the best the world has ever seen. He was a natural born artist—a true prodigy who, like Picasso, could draw untaught with amazing precision before he could barely read. His teachers arranged his first solo exhibition of his works when he was in Elementary school. Mizuki himself often downplayed his talents, as he did everything about himself. But he was an undeniable genius. Coming back from WWII an arm short, it took him many years to rebuild his ability to its previous level, but his art grew like a tidal wave as he moved from kamishibai, to manga, to gekiga, to his yokai encyclopedias.

I am sure there will be no shortage of articles recapping his extraordinary career. So instead I will give you something of Mizuki the philosopher.

Mizuki Shigeru’s Seven Rules of Happiness.

#7 – Believe in what you cannot see – The things that mean the most are things you cannot hold in your hand.

#6 – Take it easy – Of course you need to work, but don’t overdo it! Without rest, you’ll burn yourself out.

#5 – Talent and income are unrelated – Money is not the reward of talent and hard work. Self-satisfaction is the goal. Your efforts are worthy if you do what you love.

#4 – Believe in the power of love – Doing what you love, being with people you love. Nothing is more important.

#3 – Pursue what you enjoy – Don’t worry if other people find you foolish. Look at all the people in the world who are eccentric—they are so happy! Follow your own path.

#2 – Follow your curiosity – Do what you feel drawn towards, almost like a compulsion. What you would do without money or reward.

#1 – Don’t try to win – Success is not the measure of life. Just do what you enjoy. Be happy.

Mizuki Shigeru was in every way my hero. It has been my great honor to translate my hero’s comics, and share my love of him. I made a vow almost 10 years ago in a friend’s bar that I would bring this unique genius to the English-speaking world, and with Drawn & Quarterly I have made good on that vow.

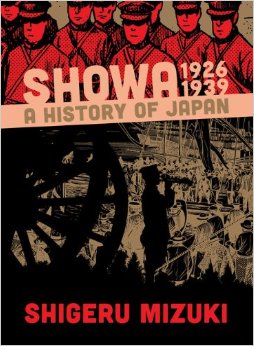

I am so happy that I was able to do this while he was still alive; it seems too often we only recognize great artists posthumously. One of my favorite photos is Mizuki holding the copies of Showa: A History of Japan that I translated, along with the Eisner Award they won for him. I now hope that we will continue to bring even more of his great legacy to a wider audience. He had so much to share.

As for Mizuki himself, he did not fear death, and saw it as a natural part of a world that was full of mystery and wonder. Decades ago he designed and commissioned his own tomb, which he has referred to in interviews as his new home.

He would often make jokes that he would be moving into his new home soon. I hope he finds it as comfortable and jolly as he had hoped. I am sure he is enjoying his well-earned rest amongst his yokai friends. They have been waiting for him for a long time.

お疲れ様でした、先生。 Goodbye, Teacher.

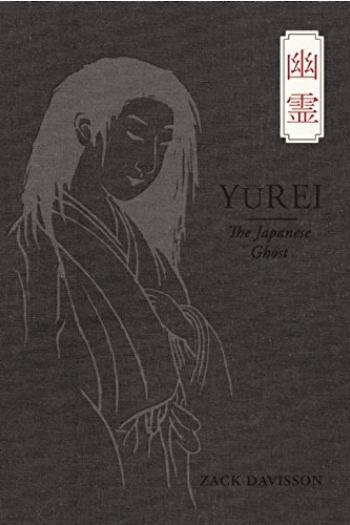

Zack Davisson

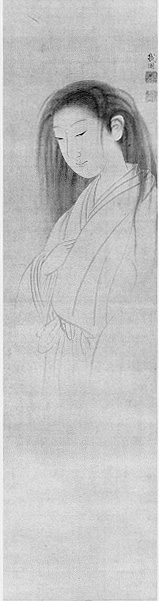

(Art by my friend Benjamin Warner. Thanks for that, Ben. You made me cry again, you jerk. But it’s beautiful.)

Here are Mizuki Shigeru’s works in English as currently available. If you haven’t already, please give them a try. The more you read, the more we can make.

NonNonBa

Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths

Kitaro

Showa 1926-1939: A History of Japan (Showa: A History of Japan)

Showa 1939-1944: A History of Japan (Showa: A History of Japan)

Showa 1944-1953: A History of Japan (Showa: A History of Japan)

Showa 1953-1989: A History of Japan (Showa: A History of Japan)

Shigeru Mizuki’s Hitler

The Birth of Kitaro

Kitaro Meets Nurarihyon

Drawn & Quarterly: Twenty-five Years of Contemporary Cartooning, Comics, and Graphic Novels

Recent Comments