Translated and sourced from Yokai Jiten and other sources.

To learn more about Japanese Ghosts, check out my book Yurei: The Japanese Ghost

Teruteru Bozu, the small tissue-paper men, are a not unusual site on overcast days in Japan. Looking exactly like the tissue-paper ghosts American children make on Halloween, they hang from the eaves of houses, each one a wish for sunny weather from a child who wants to go outside and play.

But what the children don’t know—and most likely the parents don’t know either—is that what looks like a simple folk-custom is actually a prayer to ancient Chinese gods and to one of Japan’s monster clan, the yokai called Hiyoribo.

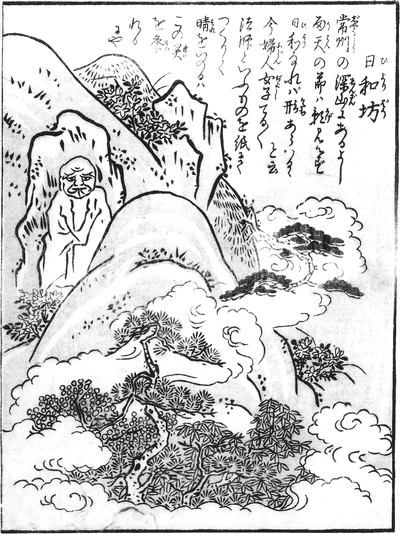

Hiyoribo (日和坊)– The Weather Monk

Hiyoribo is a legend that has been passed down for many years in Japan. He is said to come from the mountains of Hitachi-no-kuni—modern day Chiba prefecture—and his season is the summertime. Hiyoribo is said to be a yokai who brings sunny weather, and who cannot be seen on rainy days.

Toriyama Seiken illustrated the Hiyoribo in his picture-scroll “Supplement to the Hundred Demons of the Past,” and explained that this yokai was the origin of teruteru bozu. He said that when children hang up teruteru bozu and pray to them to bring sunshine into the rain, it is actually the spirit of the Hiyoribo that they are praying to.

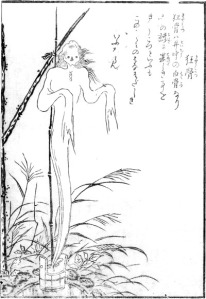

Teruteru bozu (てるてる坊主) – The Sunshine Monk

Teruteru bozu are made from white cloth or tissue bound together with a bit of string. They are usually hung upright from the eaves of a house, and are used as talisman in the hopes that tomorrow will bring good weather.

In some areas of Japan the dolls are used by farmers on days when they hope for rain instead of sun. The dolls are are hung head-downwards and called furefure bozu or ameame bozu (both meaning roughly The Rain Monk) or ruterute bozu which is simply teruteru bozu said backwards.

And although teruteru bozu is the most common name, they are also known as teretere bozu and sometimes hiyori bozu. Researcher Miyata Noboru has found that in certain places in West Japan they are still called Hiyoribo and remembered as yokai.

Teruteru bozu appeared around the middle of the Edo period in Japan. In the book “Kiyu Shoran” (Inspection of Diversions) the author writes of the custom that if the teruteru bozu is successful, and the following day is clear, then its head is washed with sacred sake and the doll is sent into a river to be washed away. In Edo period Japan, rivers were thought to connect to the afterlife and the realm of the gods, so sending the teruteru bozu down the river was returning it home in the same way that candles and lanterns were floated down the river during Obon, the Festival of the Dead. There was also a custom where—as with Daruma dolls—a face was only drawn on the teruteru bozu if it had been successful in bringing fair weather.

The origins of the custom are vague. Some say that it comes from China, where untou ningyo (cloud-clearing dolls) and ameku musume (rain banishing girls) are just a few of the similar customs that can be found. Folklorist Fujizawa Morihiko sees the origin of both the yokai Hiyoribo and the teruteru bozu in a Chinese drought-god with similar properties.

The Teruteru bozu Song

Like many Japanese customs, there is a warabe uta—a folksong. The lyrics are allegedly about a story of a monk who promised farmers to stop rain and bring clear weather during a prolonged period of rain which was ruining crops. When the monk failed to bring sunshine, he was executed.

| Japanese: てるてるぼうず、てるぼうず 明日天気にしてをくれ いつかの夢の空のよに 晴れたら金の鈴あげよてるてるぼうず、てるぼうず 明日天気にしてをくれ 私の願いを聞いたなら 甘いお酒をたんと飲ましょてるてるぼうず、てるぼうず 明日天気にしてをくれ それでも曇って泣いてたら そなたの首をちょんと切るぞ |

Romaji:

Teru-teru-bōzu, teru bōzu Teru-teru-bōzu, teru bōzu Teru-teru-bōzu, teru bōzu |

Translation: Teru-teru-bozu, teru bozu Do make tomorrow a sunny day Like the sky in a dream sometime If it’s sunny I’ll give you a golden bellTeru-teru-bozu, teru bozu Do make tomorrow a sunny day If you make my wish come true We’ll drink lots of sweet sakeTeru-teru-bozu, teru bozu Do make tomorrow a sunny day but if it’s cloudy and I find you crying (i.e. it’s raining) Then I shall snip your head off |

Translator’s Note

This is one of those ubiquitous pieces of folk magic in Japan that people have long forgotten the origins. They look exactly the same as the tissue ghost puppets I made as a child, but with very different intent!

When I lived there, I saw teruteru bozu all over the place but no one could really explain what they were or why they made them. All they knew is that little kids made them to pray for the rain to stop when they wanted to go outside and play.

I went digging and found the yokai origins of the little cotton charms.

Recent Comments