Translated and Sourced from the Mizuki Shigeru’s Mujyara, Japanese Wikipedia, An Explanation of the Tateyama Mandala and the Tateyama Faith, and Other Sources

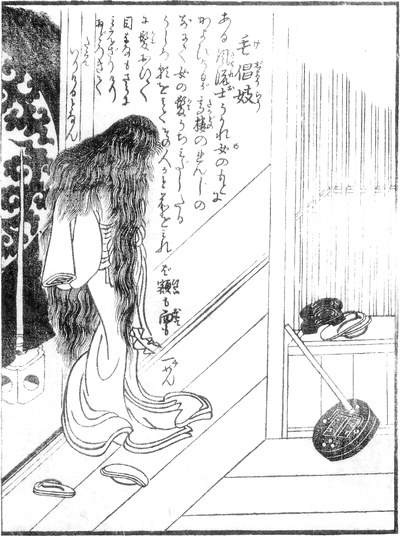

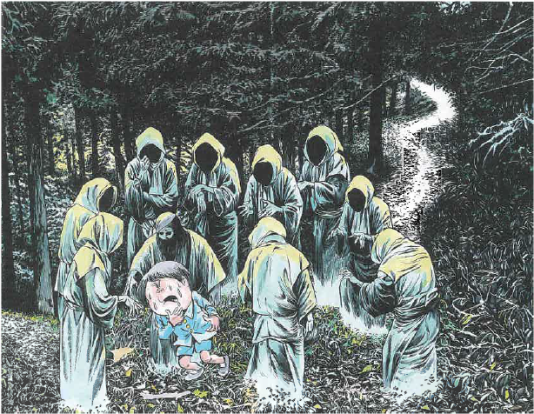

The great Hida mountain range of stretches between Gifu and Nagano prefectures. In the mountain range, on the summit of Mount Norikura, lies the Swamp of Senchogahara. One day the mountaineer Uemaki Taro was traveling near Senchogahara, when he came on a group of men and women together—about 10 of them—drinking from the swamp water.

Uemaki was justifiably terrified when he saw their were wearing the white katabira robe and triangle hat that are the garb of yurei. He was even more terrified when the group of yurei looked up and saw Uemaki watching them, and their eyes began to glow red as if on fire. Uemaki closed his eyes tight against the terrible sight and chanted the Amida Buddha’s name over and over again. With this display of devotion, the horrible ghosts vanished instantly.

Uemaki reasoned that the ghosts were making their trip to the Hell Valley of the sacred Mount Take, and had stopped to appease their thirst along the way. When he returned from the mountains, he told others of his terrifying tale and warned them of wandering ghosts on Mount Norikura. Over the years Uemaki’s story passed into legend, and the ghosts of the mountain became known as the Shoraida (精霊田)—the Rice Paddy Ghosts.

Translator’s Note:

Another Halloween tale of Japanese ghosts! This one is short, but has a few unusual characteristics. First is the name. The kanji used here–精霊田—is unusual. Well, the reading is unusual. Normally the kanji 精霊 is read either Seirei or Shoryo (See What is the Japanese Word for Ghost?) This is the only instance I know of it being read Shorai. Also the kanji 田 (ta; rice paddy) is an odd addition since the yurei appear at a swamp (沢) and not a rice paddy. But Japanese yokai have never been known for adhering to strict naming conventions.

Also, this is another tale of Tateyama (立山; Mount Tate). Tateyama—whose name translates as “standing mountain” has a long history of ghosts and the supernatural. Along with Mount Fuji and Mount Haku, it is one of the “Three Holy Mountains of Japan (三霊山)” and was the center of its own religions cult from the Heian period to the end of the Edo period.

Photo of the Tachiyama Jigokudani from this personal blog

Photo of the Tachiyama Jigokudani from this personal blog

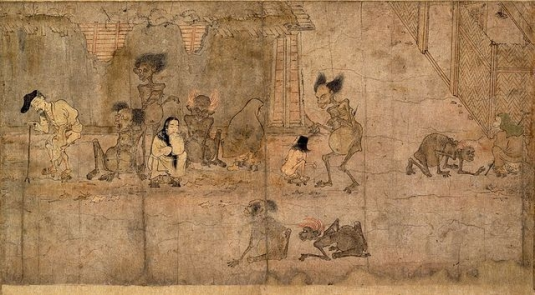

Up near the summit of Tateyama is a placed called Jigokudani (地獄谷)—Hell’s Valley. The place earned its name due to the desolation of its volcanic rock surface and the sulfurous steam that pours of vents in the mountain. There are also several mineral-laden pools of boiling water that are a deep red color and called Lakes of Blood (血の池; Chi no Ike). This references a specific level of Hell in Japanese Buddhist mythology, and there are several “Chi no Ike” across Japan.

Image of the Pool of Blood sold to pilgrims to Tateyama. Image comes from the Tachiyama Museum

Image of the Pool of Blood sold to pilgrims to Tateyama. Image comes from the Tachiyama Museum

Around the Heian period a religion sprang up based on the Tateyama Mandala, which showed a map of the mountain including pilgrimage sites. Tateyama was considered an actual portal to Hell and the gods, and someone walking the true path would find themselves in the welcoming arms of the Amida Buddha. Itinerant priests and aesthetics would carry copies of the Tateyama Mandala with them to preach the faith, and through a form of sympathetic magic guide the faithful through the map of the mountain which was said to have the same benefit as making the pilgrimage itself.

Stories sprang up based on the Tateyama Shinko (立山信仰Tateyama Faith), including ones of bands of yurei taking the trip together to the far mountain. It is implied from most of these stories that the dead are on their way to the Jigokudani instead of the merciful arms of Amida. But you shouldn’t feel too bad for them. Later variations of the Tateyama Shinko placed the every-helpful Jizo in the Jigokudani, allowing the suffering a final way out of their plight and into the Western Pure Land.

Further Reading:

For more Japanese ghost stories, check out:

Gatagata Bashi – The Rattling Bridge

Chikaramochi Yurei – The Strong Japanese Ghost

Recent Comments