Translated and sourced from Mizuki Shigeru’s Mujyara, Japanese Wikipedia, Kaii Yokai Densho Database Japanese Performing Arts Resource Center, and Other Sources

A sea serpent so massive it takes three days to pass by in a boat? Mysterious lights floating by the beach? A generic term for ghost stories? Ayakashi is one of the most complicated and convoluted terms in all of Japanese folklore. There is no easy answer to this simple question.

What Does Ayakashi Mean?

Usually when investigating a yokai I like to start with deciphering the kanji that make up the name. That is your first, best clue as to what the monster or phenomenon is. But ayakashi is written either in hiragana (あやかし) or katakana (アヤカシ), neither of which give any hints as to the meaning. There is an alternate and specific spelling of ayakashi that does use kanji, and we will look into that later.

In its most basic usage, ayakashi is a general term for yokai that appear above the surface of the water, and can be translated as “strange phenomenon of the sea.” That fact that this is the surface of the water is important—yokai tend to appear at boundaries, places where one thing becomes another thing. So ayakashi are yokai that haunt the boundary between the ocean and the air, instead of sea monsters swimming in the dark depths.

There are many yokai that have been called ayakashi over the years. Here are a few of them:

Ayakashi no Kaika – The Strange Lights of Ayakashi

In Nagasaki, the term ayakashi refers to strange lights that dance above the surface of the water, and are found mostly on the beaches in twilight.

These lights are different from the typical Japanese kaika (怪火; strange lights), in that the floating fires are said to contain what looks to be small children running around inside of them. This phenomenon is particularly associated with Tsushima city, Nagasaki.

Some of these ayakashi no kaika also appear out on the water, where it is said they can suddenly take on the appearance of massive rocks or landmasses that appear out of nowhere. The goal of this transformation is to panic ships, forcing them to change course and run aground or sink. But the irony is, if the brave captain sails right through the mirage, they vanish leaving everyone unharmed.

Funa Yurei – The Boat Ghosts

See Funa Yurei – The Boat Ghosts

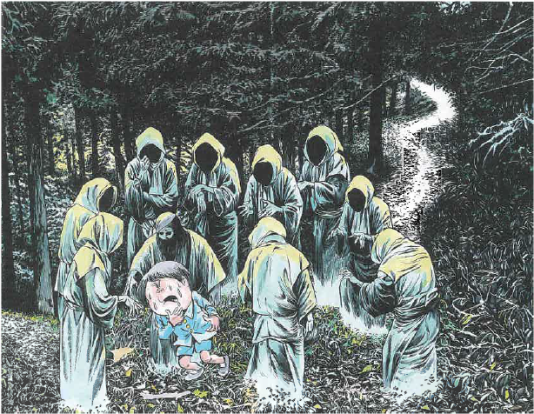

In Yamaguchi and Saga prefectures ayakashi refers to funa yurei, a group of yurei who drowned at sea and now try to sink boats to increase their numbers. Funa yubrei are known to float up to the surface of the water appearing first as kaika, then transforming into figures when they reach the surface. They will demand a hishaku—a bamboo spoon—from any boat they encounter, and if given one they will swiftly fill the boat with water and drag the crew down to the depths.

A wise captain always carried a hishaku with holes drilled in it when sailing in funa yurei infested waters. Giving this spoon to the funa yurei means that they cannot sink your boat.

Several other areas in Western Japan use the term ayakashi to describe ghosts of those drowned at sea, who try to sink boats and drown swimmers either for revenge or to swell their ranks. A good example of this is the Shudan Borei.

The Woman of the Well

This story of the ayakashi appears only once, in the Edo period Kaidanshu Kaidanro no Sue (怪談老の杖; A Cane for an Old Man of Kaidan).

In Taidozaki, in the Chosei district of Chiba prefecture, a group of sailors put to show in order to re-stock their fresh water holds. As they pulled into the beach, a beautiful woman came walking by carrying a large bucket. She said the bucket was filled with fresh water that she had drawn from a nearby well, and that she would be only too happy to share it with the sailors.

Hearing this, the Captain said “There’s no well nearby. I’ve heard similar stories of thirsty sailors beguiled by a beautiful woman offering them water, never to be seen again. That woman is an ayakashi!” He ordered the boat swiftly back to the sea. As the men pulled their oars, the woman came running towards the ship in a rage, and leapt into the ocean biting the hull of the ship and holding on tight. The quick-thinking Captain beat her off with one of the oars, and the ship sailed away unharmed.

Remoras

A real-life animal associated with the term ayakashi are remoras, the leach-like fish with sucker bellies that fasten themselves onto sharks and other ocean-going objects in order to get a free ride and some free food.

According to folk belief, if remoras fasten themselves to the underside of your boat, you will become stuck in the water and unable to move. In this case, remoras are called ayakashi.

Ikuchi – The Oily Sea Serpent

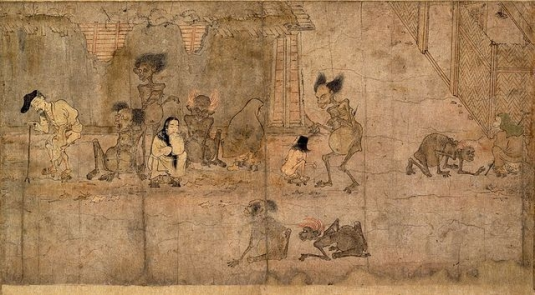

By far the most famous depiction of ayakashi is the massive sea serpent Ikuchi. The association comes from Toriyama Seiken (鳥山石燕), and his entry for ayakashi in his Konjyaku Hyakki Shui (今昔百鬼拾遺; A Collection of 100 Ghosts from Times Past)

Toriyama wrote:

“When boats sail the seas of Western Japan, they encounter a beast so large it takes 2-3 days just to sail past. The body of the beast drips oil, but if the sailors work together to clear the boat of the oil no harm will come to them. If they don’t, they will sink.“

The Ikuchi is a legendary monster from Ibaraki prefecture, that was written about in Edo period Kaidanshu like Tsumura Soan (津村正恭)’s Tankai (譚海; Sea Ballads) and Negishi Shizumori (根岸 鎮衛)’s Mimibukuro (耳袋; Ear Bag). The Ikuchi is described as eel-like and massively long, several kilometers at least. It was not inherently dangerous, but would become tangled up with ships accidently. Crews had to work often for days to get their ship free of the Ikuchi. The most dangerous part was the oil that seeped from the monster’s body. The crew had to diligently clean up all the oil, or the ship would sink.

Why Toriyama called his depiction of the Ikuchi “ayakashi” isn’t known. Perhaps he didn’t know the monster’s true name, or perhaps he was using the general term for sea monsters instead of the specific name of Ikuchi. But for whatever reason, such is Toriyama’s influence that Ayakashi has come to describe the Ikuchi in most modern depictions.

Other Depictions

The word ayakashi has been put on almost every variation of sea monster you can think of. The 1918 book Dozoku to Densetsu (土俗と伝説; Local Customs and Legends) describes the ayakashi like this:

“The ayakashi is a mystery of the sea. They haunt boats on the open waters. Their appearance is like an enormous octopus. It will wrap itself around a boat, and only let go when gold coins are given to it.”

The 1923 book Tabi to Densetsu (旅と伝説; Travels and Legends) says this about ayakashi:

“While traveling the open sea at night, you will see lights in the distance. A ship approaches, mysteriously traveling against the wind. The ship is blazing, covered in lanterns of every shape and size, and suddenly overtakes your vessel. Or sometimes it disappears all together, and reappears next to you. The boat is filled with the souls of those who drowned at sea, and they want to add to their number. If they get close enough, they will fling an iron basket filled with fire onto your ship, killing all on board.”

Another Edo period kaidanshu offers this description:

“When the winds blow from the West, the dead travel on the waves. With lanterns hanging from the prow, you can make out the site of a woman clad in a white kimono, standing in the prow of a small ship. This is the ayakashi.”

There are many, many more. Most of the stories are slightly similar—describing either some kind of great sea monster, or a boat full of drowning victims out for revenge—but few of them are exactly the same. This is probably what cause folklorists and storytellers to throw up their hands and say “Fine! Ayakashi just means all sea weirdness. That covers everything, right?”

Not quite …

Ayakashi and the Masks of Noh

While no one agrees on exactly what kind of ocean phenomenon ayakashi is, they are all at least agreed that it is SOME kind of ocean phenomenon. Except for Noh theater.

Many of Japan’s arts have a specialized vocabulary that is used nowhere else (try going to a sushi restaurant in Japan and asking for some “purple” and you will see what I mean.) As you know (ha ha!) Noh theater uses masks. All of the masks have names, and the name for a male mask of a ghost or violent god is called ayakashi.

Noh uses a specialized kanji, 怪士 meaning strange (怪; ayaka – ) + warrior (士; shi). These masks come in variation, like the chigusa ayakashi which is fleshy and more human-like, or the shin no ayakashi with protruding eyes and bulging blood vessels. The most terrifying is the rei no ayakashi, a skeletonesque face with a white pallor and sunken eyes. The ayakashi masks were designed around the Muromachi period and where used interchangeably for many ghostly roles, but by the Edo period each mask had been assigned a specific role.

Because of the masks of Noh, and Ayakashi no Mono (怪士のもの) can refer to a ghost story of Noh, where one of the ayakashi masks are used. And that is where the confusion comes in, from using the term “ayakashi” as a general word for yokai or “ghost story.” It is … but ONLY in Noh theater.

Ayakashi: Samurai Horror Tales

And that brings us to where most Westerners have heard the term ayakashi, in the anime Ayakashi: Samurai Horror Tales. While this is a brilliant series, you will notice that nowhere is there a sea creature of any kind, neither monster nor boat full of lantern-bearing yurei.

That is because the series is named after the Noh usage of ayakashi, which gives it a mysterious, nostalgic feel (and is also a bit misleading, as the stories in Ayakashi: Samurai Horror Tales come from Kabuki theater and not Noh. But that’s marketing for you … )

Translator’s Note

This started out with me answering a reader’s question on the difference between yokai, ayakashi, and mononoke. It soon became apparent that there was far too much information for a simple answer, and blossomed into this article.

And I still didn’t answer the question! Sorry! But at least you will have a better understanding of what ayakashi means!

Further Reading:

For other informative posts about yokai and such, check out:

What Does Yokai Mean in English?

Recent Comments