Translated and Sourced from Mizuki Shigeru’s Mujyara, Japanese Wikipedia, and Other Sources

Snow and ice have a certain magic to them. You can craft them into whatever shape you want, from snow men to snow wives to snow babies. And—legend tells us—if you wish hard enough, they just might come to life. But snow is fickle. To an elderly childless couple, it might bring joy and comfort—but only for a little while. Spring comes and snow melts and takes the beauty and magic with it. That is the lesson of the story of the Yuki Warashi.

The Yukinbo, however. tells an entirely different kind of story …

What Do Yuki Warashi and Yukinbo Mean?

Both of these snow babies’ names mean roughly the same thing, just using different kanji

- 雪童子 – Yuki Warashi – Combines雪 (yuki; snow) + 童子 (warashi; small child). Sharp-eared readers will recognize this as using the same kanji as the good luck house spirit Zashiki Warashi.

- 雪坊 – Yukinbo – Combines雪 (yuki; snow) + 坊 (bo; priest). Note that by itself “bo” is a slang term for young boys, like the diminutive “Bo-chan.” Of the two names, only the Yukinbo specifies a gender.

What Do They Look Like?

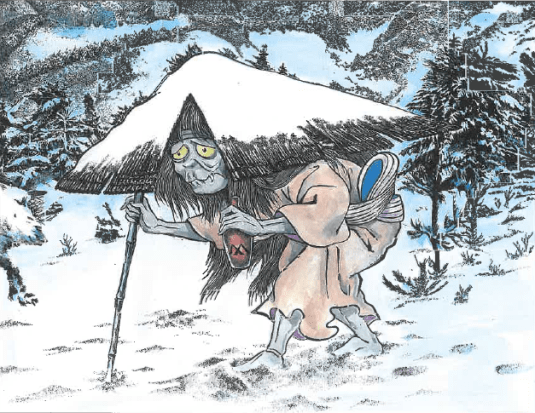

Images of the Yuki Warashi and Yunkinbo are exceedingly rare. When they do appear, they look like cute, red-cheeked children clad in the traditional straw-peaked snow jackets. Their jackets have a hood that comes up to a point so that the snow can’t accumulate. The hood ties under the chin, and there are armholes that give freedom of movement.

From the children’s book お化けの冬ごもり (Obake no Fuyu Gomori)

In some Yuki Warashi depictions their face is blank and featureless like a doll. This comes less from folklore and stories and more from folk art. Wooden sculptures of children dressed in this ancient costume are popular. In fact, people in snowy regions still dress their children in these costumes for pictures. After all, they are awfully cute. But not every child in a straw snow coat is snow baby.

Definitely not a Yukinbo, unless they are hopping on one leg …

Yuki Warashi – The Good Little Snow Child

This is a legend from Nigata prefecture.

Long ago there was an old, childless couple. They were very lonely, and wished desperately for a child. One snowy day, in order to distract themselves from their desolation, they went out into the new fallen snow and sculpted a snow child. Pleased with their creation, they went back inside.

That night there was a fierce blizzard. There was a knock and the door, and when they answered it the couple were shocked to see a bright, young child leap into their house. They were too overjoyed to question their good fortune, and welcomed the child into their hearts. They loved their snow baby, and vowed to raise it with affection.

The new family passed a wonderful winter together, but as spring neared the couple noticed that their child got slimmer and slimmer. They were terribly worried, and woke up one morning to find their child gone completely. Their hearts were broken, but there was nothing they could do.

Time passed, and soon it was winter again. On yet another storming snowy night, there was a knock at the door and the couple’s happy snow baby came bounding home again, fat and happy and red-cheeked. The couple realized that this was the spirit of the child they sculpted out of snow, could only stay with them through the winter.

This pattern repeated itself for many years, until one day the snow baby came no more. They never saw their child again. But the couple was content with what happiness the kami allotted them, and forever cherished the sweet memories of their snow baby.

Yukinbo – The One-Legged Snow Boy

The Yukinbo comes from Wakayama prefecture, and is essentially a personification of a natural phenomenon.

As anyone who lives in a snowy climate—or participates in winter sports—knows, the snow around trees and plants melts faster than elsewhere. We call these “tree wells” when skiing, and falling into a tree well can be a dangerous proposition. You sink into the semi-melted snow and can have a hard time tunneling back out.

Strangely, there is no real known scientific explanation for this. Oh, there are theories to be sure, most amounting to internal heat generated by the plants. But there is no absolute answer (At least not according to Susan Pell, director of science at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden.)

But the people of Wakayama didn’t need science. They knew tree wells were cause by a one-legged yokai called the Yukinbo who came out in the morning and hopped circles around trees.

Translator’s Note:

More snow monsters for December! Although they aren’t really related, I decided to combine the Yuki Warashi and Yukinbo into a single entry. Mainly because they are both obscure, without much detail to their stories and descriptions. Also because of a lack of pictures. I wasn’t able to find a single picture of a Yukinbo. Neither of them appear in my volumes of Mizuki Shigeru’s Mujyara, except as footnotes to other yokai, nor do they appear in Toriyama’s catalogs of any other yokai resource. But they are cool legends, so I decided to add them to the series.

The Yukinbo in particular gave me some trouble. As a one-legged snow monster he shares and almost identical story to the Yukinba and Yuki Nyudo. I considered sticking them all together, but eventually went with age/gender instead of number of limbs. The Yukiba went with the Yukifuriba, and the Yuki Nyudo will go with the Yukifuri Bozu (If I have time to get around the them!)

Related Stories:

For more December yokai chills, check out:

Tsurara Onna – The Icicle Woman

Recent Comments