Translated and sourced from Kitaro’s Daihyaka, Mizuki Shigeru’s Mujyara, Japanese Wikipedia, and various Gegege no Kitaro comics

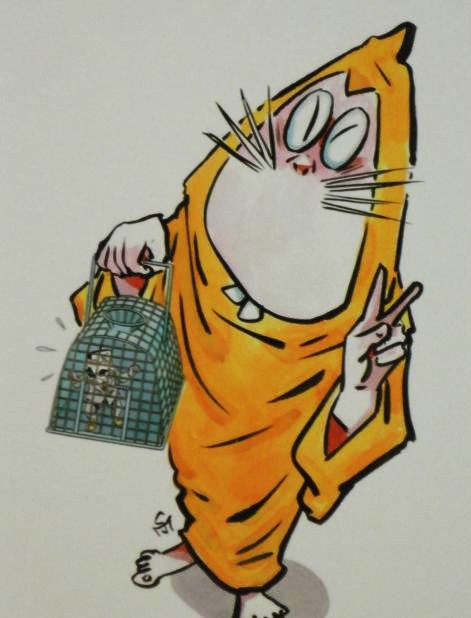

Half yokai. Half human. All scoundrel. Nezumi Otoko is the trickster character in Mizuki Shigeru’s seminal yokai comic Gegege no Kitaro. Filthy, greedy, and conniving, Nezumi Otoko sides with whoever looks like they will come out on top, and yet he always manages to be back with Kitaro for the next adventure. Even though his constant schemes and betrayals earn the ire of everyone around him, Mizuki Shigeru has long said that Nezumi Otoko is his favorite character and that without Nezumi Otoko Gegege no Kitaro could not exist.

What Does Nezumi Otoko Mean?

Almost all sources (including this article) give Nezumi Otoko’s name as “Rat Man” in English, but this is not technically correct. This translation is based on a pun in Japanese and his appearance rather than his actual name. The truth is more complicated.

Written in Japanese, his name is ねずみ男 (Nezumi Otoko). Sharp-eyed readers will notice that while he uses the kanji for “man” (男; otoko), he doesn’t use the kanji for “rat” (鼠; nezumi). Because “nezumi” is written in hiragana, there is no inherent meaning. One those rare occasions where kanji is used, Nezumi Otoko’s name is given as 根頭見 (根; ne – root,) + (頭; zu – head) + (見; mi – look). So, a transliteration of would be “Guy With the Root-Shaped Head.” If you look at him, that fits pretty well. But it’s more of a mouthful than “Rat Man.”

Even then, Nezumi Otoko is only a nickname. In one adventure where the Kitaro gang journeyed to Nezumi Otoko’s homeland, his true name was revealed as Nezumi Pekepeke (根頭見ペケペケ). This was an inside joke Mizuki Shigeru made to himself, as “pekepeke” is the word for “shit” in the language of the Tolai people of New Guinea where Mizuki once lived. Nezumi Pekepeke is one of those “secret facts” that show up on yokai quizzes. For all intents and purposes, his name is Nezumi Otoko.

Nezumi Otoko has one more nickname, Bibibi no Nezumi Otoko (ビビビのねずみ男). This is a play-off of Kitaro’s own nickname Gegege no Kitaro, and refers to the onomonopiac sound of slapping someone in the face (which Nezumi Otoko does often). He is also known to use the pseudonym Nagai Futen in his schemes, and has a passport and documentation in that name.

The Origin of Nezumi Otoko

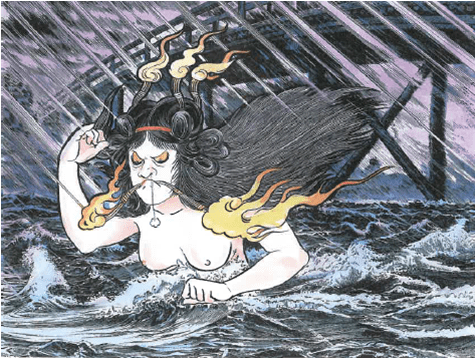

Nezumi Otoko is a half-yokai, what Mizuki Shigeru calls a hanyokai and what Takashi Rumiko calls a hanyo. But even though he is half-yokai / half-human, the accounts of his birth vary and the human half is never explained.

In the most official version, the one used for his profile in Kitaro’s Daihyaka (鬼太郎大百科), Nezumi Otoko was mysteriously born as a human baby on an island populated only by rats. That’s it. End of story.

In another story, Kitaro’s Hell Compilation (鬼太郎地獄編), Nezumi Otoko comes from a land on the boarder of the world of the living and the world of the dead. This world is populated by people like himself, and “Nezumi Otoko” is a general term for the species. Nezumi Otoko’s mother appears in this story, looking like female version of the rat man himself. But she is later revealed to be Sasori Onna in disguise as part of a revenge plot by Nurarihyon. However, Nezumi Otoko’s world and people are never referenced again outside of Kitaro’s Hell Compilation.

About Nezumi Otoko

Whatever his origins, Nezumi Otoko is a true yokai. He is over 360 years old, and likes to claim that he has never taken a bath in all that time (which is untrue, like almost everything Nezumi Otoko claims). His body is repulsive, covered in ringworm and scabies, and is home to unique diseases that evolved to live only in Nezumi Otoko. He can eat anything, no matter how rotten or unpalatable.

His most powerful weapon is his own filth. Nezumi Otoko’s breath is so foul it can knock people out cold, and he can fart with the power of a rocket blast. In some stories, he is even able to fly by spreading out his cloak and farting, using the hot air to take off. His cloak is as dirty as he is, and can also be used as a weapon based on its stink alone.

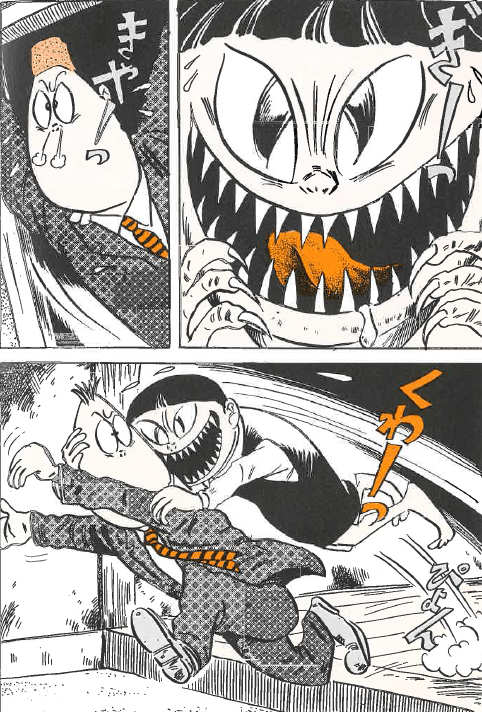

He has other random weapons in his arsenal—his rat-like teeth are sharp enough to bite through things, and his long whiskers have been shown to be as strong as iron. He is quick with a slap, earning his nickname Bibibi no Nezumi Otoko. Mizuki Shigeru has a tendency to make things up as he goes along, so Nezumi Otoko might unveil some special power for one story, never to be mentioned again.

Even though he isn’t officially “Rat Man,” his rat-like nature is enough to excite the appetite of the cat girl Neko Musume and other cat yokai. Cats are Nezumi Otoko’s natural enemies, and he is terrified of them.

Nezumi Otoko – For Love or Money

Money is Nezumi Otoko’s main motivation, and he is constantly scheming to acquire it even though it always slips through his fingers.

Whenever possible, he secretly charges people for Kitaro’s help or even sells humans to monsters if the price is right. As part of his schemes, Nezumi Otoko claims to be a degreed professor from the prestigious Yokai University and deeply knowledgeable about all things yokai. This isn’t a complete lie, and it is often speculated that Kitaro and Nezumi Otoko met as co-students at Yokai University. (Although Nezumi Otoko’s graduation is dubious).

The other thing that drives Nezumi Otoko is his quest for love. In many stories, he has attempted to romance some unsuspecting woman, usually though devious schemes and hiding his true nature. But, as is the case with all of his plans, the truth eventually outs and all ends in tears.

Brief Publication History of Nezumi Otoko

Like Medama Oyaji and Neko Musume, Nezumi Otoko is an original yokai creation from Mizuki Shigeru. He first appeared in the story “The Lodging House” (下宿屋) in the rental manga Hakuba no Kitaro (墓場の鬼太郎; Graveyard Kitaro). In that story, Nezumi Otoko was an unnamed servant of Dracula the 4th, and was in charge of securing lodgings and victims for his master. He disappeared halfway through the story when Kitaro and Medama Oyaji met the true menace.

He appeared again, this time officially as Nezumi Otoko, in the story “The Strange Fellow” (おかしな奴) . He presented himself to Kitaro and Medama Oyaji as a famous Yokai Professor, offering his services to them—for a modest fee, of course. Another introduction happened in the Gegege no Kitaro novel from Kodansha. Nezumi Otoko shows up out of nowhere and steals a fish dinner out from under Neko Musume. Hijinks ensue, and Nezumi Otoko is soon part of the regular group.

Nezumi Otoko’s first animated appearance was in “Yasha” (夜叉), the second episode of the first season of the animated Gegege no Kitaro. He has appeared in every series of the cartoon ever since, as well as several live-action TV shows and movies.

Nezumi Otoko has appeared in every possible medium, and on every possible product. He even has his own train. You would be hard-pressed to find anyone in Japan who didn’t know Nezumi Otoko, and he is one of the most well-known and popular characters in Japan.

Mizuki Shigeru on Nezumi Otoko

In any interview, whenever he is asked about his favorite yokai, Mizuki Shigeru is quick to answer “Nezumi Otoko.” He likes the rest of the Kitaro family about the same, but Nezumi Otoko is his favorite child. Mizuki explains “Kitaro is actually kind of dumb. He’s like Superman, giving everything he has to random strangers without hope of reward or happiness. That’s boring. If I don’t put Nezumi Otoko in there to mess things up a bit, I don’t have a story. “

Mizuki further says that his original goal with Kitaro was social commentary and satire. It was at the publisher’s request that he change his stories to focus on Kitaro as a Hero, using his supernatural powers to defeat monsters. Nezumi Otoko is the only character that embodies Mizuki’s original intentions for the comic.

Mizuki says his own life philosophy is much closer to Nezumi Otoko’s—he values money, luxury, and happiness and would never give it away for free like Kitaro does. Sometimes he uses Nezumi Otoko to voice his own opinions in a way he can’t with Kitaro. Life was exceptionally hard for Mizuki until he found his success as a comic artist, and those feelings of hunger, of failure, of grasping for success that continually eludes you, are embodied in Nezumi Otoko.

When Mizuki Shigeru wrote his own autobiography and history comic, Showa: A History of Japan, he used Nezumi Otoko as his narrator and mouthpiece.

Nezumi Otoko’s Model

Along with himself, Mizuki Shigeru based Nezumi Otoko on his friend Umeda Etaro (梅田栄太郎). Umeda worked in the rental manga market along with Mizuki Shigeru, and he was always thinking up get-rich-quick schemes to try and squeeze a little bit more money out of kids. And like Nezumi Otoko, his schemes always failed.

In the 2010 drama Gegege no Nyobo, Uragi Yoshino (浦木克夫), was also named as an influence on Nezumi Otoko.

Translator’s Note

This is my first piece in a series on yokai who appear in my translation of Showa 1926-1939: A History of Japan from Drawn & Quarterly.

In doing my translation on Showa 1926-1939: A History of Japan and my work on Kitaro

(also from Drawn & Quarterly) I gained a new appreciation of Nezumi Otoko. Just like Donald Duck and Wimpy from Popeye, Nezumi Otoko plays an important role in Gegege no Kitaro, and it is easy to see why he is Mizuki Shigeru’s favorite.

Just like Walt Disney soon learned that Mickey Mouse—while popular—was too bland of a character to carry on a story by himself, Mizuki needs Nezumi Otoko to be greedy, to betray, to do the wrong thing; all of which pushes the story forward.

Further Reading:

For more on Mizuki Shigeru and his yokai, check out:

Recent Comments