Translated and Sourced from Mizuki Shigeru’s Mujyara, Kaii Yokai Densho Database, Japanese Wikipedia, and Other Sources

Legends of a Great White Whale usually bring to mind Moby Dick, but the white of this whale is the color of its bones. For bones are all you can see of the Bakekujira—a massive, skeletal baleen whale that appeared and disappeared under mysterious circumstances once of the coast of Japan. Is it a monster? Is it a ghost? Is it a god? No one really knows for sure.

What Does Bakekujira (化鯨) Mean?

Bakekujira’s name is the same as many magical animals in Japanese folklore, with a difference of nuance. For most bake- creatures (bakeneko, bakenezumi, etc … ) the kanji 化 (bake; change) refers to a transformation, the ability to shift from one form to another. In Bakekujira—化 (bake; change) +鯨 (kujira; whale)—bake does not refer to a transformation. It just sounds scary and bizarre. This is one instance where translating bakekujira as “ghost whale” or “goblin whale” instead of “transforming whale” would be perfectly appropriate.

The Tale of the Bakekujira

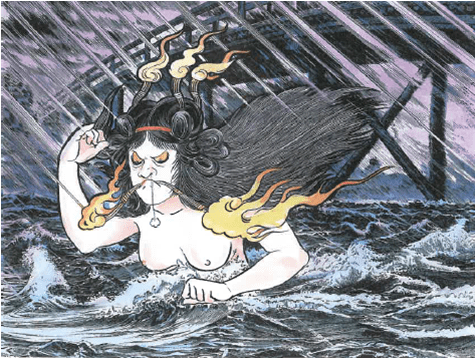

One rainy night, something massive and white appeared off the coast of Okino Island, Shimane prefecture. Fishermen from the village watched it get closer and closer, and finally decided to take a rowboat out and see what it was. From its size, they knew it must be some sort of whale, but no one had seen a whale like that before. As they rowed out their boat, they saw the waters of the ocean glimmer with thousands upon thousands of fish, the likes of which they had never seen.

As they neared the white whale, one of the fisherman threw his harpoon and it passed through the mass of white unnoticed. Their vision obscured by the pounding rain, the fishermen finally got a good look at the monster—it was the skeleton of a great baleen whale, without an ounce of skin nor meat on it. But it was moving and alive.

The men were terrified, even more so because the ocean was writhing with unknown fish, and the skies were filled with strange birds. In the distance they saw an island that hadn’t been there before, as if they had rowed into some mysterious country. Then suddenly the vision ended, and the massive bakekujira—for that is what they called it—retreated back to the open sea as quickly as it had come.

When the fishermen went back to shore, they speculated that it might have been the ghost of a whale killed in a hunt or some strange god. Whatever it was, the bakekujira was never seen again.

The History of the Bakekujira

That’s it. There is that one story of the one appearance of the bakekujira, and that is the sum total of knowledge on the boney beastie. Anything else you read about the bakekujira is pretty much just made up to try and fill in the gaps.

In fact, for being so well-known in the modern world, the bakekujira is a limited and obscure yokai. It wasn’t important enough to be added to Toriyama Sekien’s numerous Edo-period yokai collections; there aren’t any ukiyo-e prints or kaidan collections including the bakekujira—at least not that I could find when I was researching for this article. In fact, the first mention I could find of the bakekujira was from Mizuki Shigeru, whose cool character design seems largely (solely?) responsible for the bakekujira being known today.

But Japan does have a long history of whale gods and venerated bones, to which the bakekujira fits in nicely. So allow me to segue to another aspect of Japanese folklore—the Whale Cults of Japan.

Hyochakushin – The Drifting Ashore God

In pre-seafaring Japan—before Samurai William brought the secret of keels and ocean-going vessels—fishermen were limited to the coastal waters their small ships could take them too. They eked out a subsistence living harvesting what was in reach. But every now and then, the oceans would deliver a bounty beyond imagination.

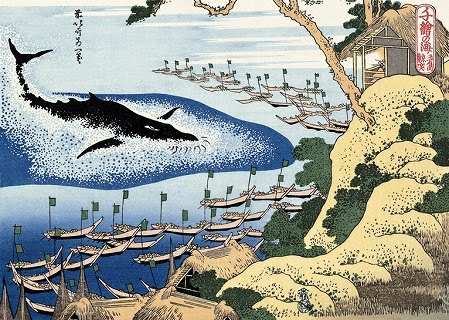

Whales would sometimes come inland, or beach themselves on the shore. Fishermen hunted these whales in a practice called Passive Whaling, using harpoons to kill the whale that was trapped in the shallows. This was a rare and auspicious event—a single whale provided vast amounts of meat and resources for the village, and seemed like a gift from the gods. And the whale itself was only a piece of the bounty. Whales often came in following larges schools of fish, so their arrival meant an abundance of sea life beyond the leviathan itself. The arrival of a whale could save a village teetering on the edge of starvation and ruin. It was mana from the oceans.

Like modern Cargo Cults, the villagers could not understand from where or why the whale came in to shore. They only knew that a whale meant wealth and rare full stomachs. Whales were considered to be embodied deities (神体; shintai), and whale religions sprang up in coastal villages, called Hyochakushin (漂着神; Drifting Ashore God) or Yorikami Shinkyo (寄り神信仰; The Religion of the Visiting Kami).

The Whale and Ebisu

These original whale cults were primitive. The people praying generally had one request—send more whales. But in time they evolved. Like many religions, the Whale Cults in Japan were built on a portion of respect and gratitude and a portion of fear. Because whaling—even Passive Whaling—was a dangerous operation, some whale religions also saw in whales the ability to be malevolent gods, and prayed to appease their spirits and assuage their wrath. Bad storms of poor catches could mean an angry whale god, and nobody wanted that.

In time, these whale religions merged with another, more popular deity, the god of abundance Ebisu. Whales were first thought to be emissaries of Ebisu, and then became considered to be an incarnation of Ebisu himself. Because whales were thought to have the power to control fish, fishermen began carrying images of the god Ebisu as a whale to give them the same fish-controlling powers.

Kujira Jinjya – Whale Shrines

When you have feasted on the body of a god, it only makes sense to give the leftovers a proper burial. After stripping the body of everything useful, villagers buried the whale carcass in mounds called Kujira Tsuga (鯨塚; whale mounds). Kujira Tsuga were capped with monuments of some sort, varying from carved stone tablets to pagodas to small wooden or rock shrines. Often these Kujira Tsuga were created in memory of some particularly bountiful harvest, and annual festivals where held like the Daihyo Tsuifuku (大漁追福; Big Catch Memorial Service). Or people prayed to the Kujira Tsuga for Kaijyo Anzen Kito (海上安全祈祷; Prayers to Ensure Safety at Sea).

Places where passive whaling was more prevalent also had Kujira Haka (鯨墓; whale graveyards) and Kujira Ishibumi (鯨碑; whale stone monuments). There are about 100 known whale graveyards throughout Japan.

Many Kujira Tsuga have their own legends and myths. In Miyagi prefecture, Kesenmema city, Karakuwa town, a legend is told of a ship foundering in the storm that was approached by two massive, white whales. The two whales swam to either side of the ship and steadied it, guiding it into port before sailing away. From that day forward, the citizens of Karakuwa down abandoned their ancient custom of whale eating.

The legend is attached to the MIsaki Shrine in Karakuwa, but the connection is not exactly accurate. Misaki Shrine is an old Kujira Tsuga, raised over a whale corpse and topped with a stone monument expressing gratitude for the whale’s death.

In Ehime prefecture, Seiyo city, Akehama town there are three known Kujira Tsuga, one of which is high up in the mountains. The shrine is ancient, and overlooks the ocean. It now sits along the national highway route making it much more accessible. Hauling up that carcass must have been quite the event.

On June 21st, 1837 (Tenpo 8th), a massive whale came to shore directly underneath this shrine. This was during the Great Tenpo Famine, and the whale saved the entire area from starvation. The villagers gave the whale a posthumous Buddhist name, meaning roughly “The Great Whale Scholar of the Universe who Brings Health.” That was extremely rare at the time, as posthumous Buddhist names was an honor reserved for great lords. The shrine is still honored by the villagers today

Whalebone Tori Gates

By the Edo period, Japan had become a seafaring nation and created a whaling industry and culture. Whaling Associations established and maintained official Whale Shrines in coastal areas, many of which still exist today. Whale shrines were also built in Taiwan when it was under Japanese rule, usually dedicated to Ebisu.

The most dramatic of these have Whalebone Tori gates—the picturesque post-and-lintel design that signifies the presence of a kami spirit.. The oldest Whalebone Tori is in Wakayama prefecture, Taijicho town, called the Arch of Ebisu. Ihara Saikaku mentions this Tori in his book Nippon Eitaigura (日本永代蔵; Japan’s Warehouse of Eternity; 1688). The tori is probably much older, however. The newest whalebone tori is in Nagasaki, Shinkamigostocho town at the Kaido Jinjya (Shrine of the Sea). Dedicated in 1973, it was built by the Japan Whaling Association.

Nirai Kanai

In an odd and unrelated Okinawan legend, a whale dressed in a kimono was said to have brought the secrets of rice cultivation to Japan. You can read more about this in my article on Nirai Kanai.

The Curse of the Bakekujira

There are two odd footnotes to the story of the bakekujira, that don’t really fit in anywhere else so I am sticking them on here at the end.

In the 1950s, manga artist Mizuki Shigeru was working on a kamishibai story about the bakekujira, and also eating a lot of whale meat. He suddenly came down with a terrible fever, that only stopped when he quit working on the story. He calls this the “Curse of the Bakekujira.”

In 1983, an intact whale skeleton was spotted floating off the shores of Anamizu, Ishikawa prefecture. The press jumped on the story naming it a “real-life bakekujira.”

Translator’s Note:

This article was done at the request of comic book writer Brandon Seifert, who does the incredibly cool folklore/horror comic Witch Doctor, as well as other things. If you are a folklore fan, I highly recommend his work. And look for the bakekujira to possibly pop up his boney head in one of Seifert’s upcoming comics!

Further Reading:

For more tales of ocean-going yokai, check out:

Recent Comments